A debtor to mercy alone

- Deuteronomy 7:9

- Psalms 103:11-12

- Psalms 111:9

- Psalms 132:9

- Isaiah 38:17

- Isaiah 43:25

- Isaiah 49:16

- Isaiah 61:10

- Jeremiah 31:31-34

- Ezekiel 37:26

- Daniel 9:4

- Micah 7:19

- Matthew 10:22

- Matthew 24:13

- Mark 13:13

- Luke 10:20

- Luke 7:40-43

- Romans 3:21-26

- Romans 5:19

- Romans 8:1-2

- Romans 8:12

- Romans 8:38-39

- 2 Corinthians 1:20-22

- Ephesians 1:7

- Philippians 1:6

- Philippians 3:9

- Hebrews 12:23

- Hebrews 5:8-9

- Hebrews 8:10-12

- 1 Peter 1:4-5

- 773

A debtor to mercy alone,

of covenant-mercy I sing;

nor fear, with your righteousness on,

my person and offering to bring:

the terrors of law and of God

with me can have nothing to do;

my Saviour’s obedience and blood

hide all my transgressions from view.

2. The work which his goodness began,

the arm of his strength will complete;

his promise is ‘Yes’ and ‘Amen’,

and never was forfeited yet:

things future, nor things that are now,

nor all things below or above,

can make him his purpose forgo,

or sever my soul from his love.

3. Eternity will not erase

my name from the palms of his hands;

in marks of indelible grace

impressed on his heart it remains:

yes, I to the end shall endure,

as sure as the promise is given;

more happy, but not more secure,

the glorified spirits in heaven.

Augustus M Toplady 1740-78

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

Tunes

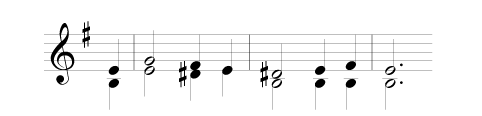

-

Covenant Blessing

Metre: - 88 88 D anapaestic

Composer: - Chapman, T H

-

Trewen

Metre: - 88 88 D anapaestic

Composer: - Evans, David Emlyn

The story behind the hymn

The previous hymn introduced a new section on ‘Assurance and Hope’. The juxtaposition of the next two brings a pair of texts with the same metre, subject matter and author—like Newton, a CofE parish clergyman who believed and preached the doctrines of grace. ‘Grace’ features in all 3 texts, not simply as a word but as a reality; but Augustus Toplady was a man of quite different temperament from Newton, and (while bearing in mind the simplicity of 772) it is tempting to trace this contrast in the language of his 2 hymns in this section. In many ways they are the greater pieces of writing; it is all the more frustrating that the inverted, even tortuous style of many lines has sometimes prevented them from being chosen, sung, or even included in a hymnal. This one, printed in the May 1771 Gospel Magazine and soon afterwards in the author/editor’s Psalms and Hymns, has become precious to each new generation discovering the truth of its words, sometimes enjoying such veneration that by being treated as untouchable it remains incomprehensible. Following others, therefore, the present editors have ventured to adapt the arrangement of its language while aiming to preserve both its theology and its literary quality. But in one sense it will never be another Amazing grace, let alone a Rock of ages.

Its original title was ‘Assurance of faith’. Cliff Knight (A Companion to Christian Hymns) is surely right to say that ‘its forcefulness in the first line arrests your attention and you are under its spell immediately.’ He may also be fair in charging Anglicans with its neglect, though HTC and Anglican Praise (1987) did something to mend that situation, and in their day both Golden Bells and Christian Praise helped to maintain its popularity among students and others. Methodists, Congregationalists and their successors have predictably been more wary. Even a century ago Julian’s comment was that ‘it is now very generally omitted from modern collections in G Brit, although in America it still holds a prominent position.’ Except for ‘promise’ replacing ‘earnest’ at 3.6, the only significant changes affect the first half of this final stz, originally beginning ‘My name from the palms of his hands …’ This text simply removes the inversions, leaving the less exact rhyme in lines 2 and 4 rather than 1 and 3. But of the 12 rhymes in all, only 3 of Toplady’s are impeccable.

Although TREWEN (see 774) is often used for these words, and less often the 88 88 CELESTE which tends to disguise or interrupt the flow of the hymn (see 788), first choice here is T H Chapman’s COVENANT BLESSING. Among current books this strong tune of c1900 seems to feature only in GH, set to this hymn for which it may have been written. Its composer is little-known, and does not feature in the 1977 Check-List compiled by Hayden and Newton.

A look at the author

Toplady, Augustus Montague

b Farnham, Surrey 1740, d Kensington, Middx (W London) 1778. Named after his two godfathers on the insistence of his godmother, he attended Westminster Sch, London (briefly overlapping with the older Wm Cowper) and Trinity Coll Dublin (MA). Like John Wesley whom he later came to oppose, he owed much to his mother, his soldier-father having been killed in a siege before Augustus was born. ‘Mamma’ was also a refuge from an unpleasant aunt, notably during his recurring illnesses. But in 1756, attending a meeting in a barn at the age of 16 in the variously-spelt Cooladine in the parish of Ballynaslaney in the Irish countryside, he was converted through the ministry of James Morris. Morris was a gifted Methodist (later a Baptist) evangelist; a lay preacher but probably not so illiterate as AMT afterwards recalled. The crucial text was Eph 2:13, and his life took a new direction from then onwards. Strengthened in his grasp of Reformed doctrine by feasting on Thos Manton’s printed sermons from John 17 and Geo Whitefield’s preached ones in London, he published a teenage collection of verse in 1759, Poems on Sacred Subjects, with an assured touch but in highly personal ‘I/me’ mode. Without an obvious mentor, a striking opening (‘Chained to the world, to sin tied down’) can descend into absurdity (‘Put on thine helmet, Lord’; ‘O when shall I my God put on?). In 1762 he was ordained in the CofE, but resigned his first parochial charge at Blagdon, Som; he ministered for 16 months at Farleigh Hungerford nr Bradford-on-Avon. A short break was followed by two years in the small and mainly poor villages of Harpford and Venn Ottery, Devon, until he was appointed in 1768, in an exchange of benefices, to Broad Hembury (also spelt as one word), nr Honiton in the same county. Newly recovered from some days of distress and depression (‘the disquietness of my heart’), by now his life was already marked by voracious reading, eloquent preaching, single-minded piety, feverish controversy, occasional hymnwriting, and alarmingly fragile health. His ministry began to achieve remarkable results, but he also fought battles in print with the perfectionism and Arminianism of John and Chas Wesley, writing while standing at his high desk. Where he saw gospel truth at stake, he believed ‘’twere impious to be calm’; 1769 saw the publication of his translation of Jerome Zanchius (1516–90) on predestination, which provoked J Wesley to conspicuous lack of calm in his mocking rejoinder, and so the battle hotted up.

In 1775 Toplady first met Lady Huntingdon and began to preach widely in her chapels, but he was already a sick man. For health reasons he was now able to move from Devon, employing a curate there while he ministered as ‘Lecturer’ at London’s Orange St Chapel in Leicester Fields (between Trafalgar Sq and Leicester Sq) for just over 2 years, the last of his meteoric life as chest pains and other ailments multiplied. This 1693 building was owned and still used by French Reformed Protestants, but licensed for CofE services by the Bp of London, for Toplady’s sake; congregations of both rich and poor overflowed. On 19 April 1778 he could barely croak out his text before withdrawing; it was 2 Pet 1:13–14. But on 14 June, close to death, he spoke with great difficulty, to reaffirm his convictions in the doctrines of grace, which were later printed as a pamphlet. He died two months later at the age of 37, still glorying in Christ but still aiming verbal darts at Wesley, who for his part did nothing to correct the hostile rumours surrounding Toplady’s final hours.

While there were faults and blind spots on both sides, the ‘natural’ friends of Toplady’s doctrinal position now regret that his fiercely-expressed convictions (probably aggravated by illness) provided any justification for John Wesley’s equally aggressive attacks and slanderous accusations. Dr Samuel Johnson remained the friend of both men, and AMT and JW shared an ‘almost uncontrollable passion’ (Lawton) for radically ‘improving’ other people’s hymns—in which they were not alone. Toplady also resembles Chas Wesley in his disciplined rhyming and the occasional indulgence in a rolling Latinism. Occasionally he rises to the heights of Watts; often too a comparable Britishness (identifying the ‘rogue states’ and ‘axis of evil’ of his day) led him into verses rarely sung then, let alone now: ‘Let France and Austria weep in blood;/ just victims of the sword of God’! While maintaining a warm and respectful friendship with Dissenters, notably the Baptist Dr John Gill of Carter Lane, Southwark, Toplady like his other hero Wm Romaine was always fiercely Anglican, appealing often to its Thirty Nine Articles of Religion and other formularies. Part of his own apologia was The Historic Proof of the Doctrinal Calvinism of the Church of England, 700 pages issued in 2 volumes in 1774 to provide theologically heavyweight grounding for the preaching and writing of George Whitefield, who had died in 1770. In 1775 he took over editorship of The Gospel Magazine (‘pompous…pestilential’—J Wesley) for which he wrote, wittily but in the end obsessively, over various initials, until 1777; in 1776 came Psalms and Hymns for Public and Private Worship, which among its 419 items included many vivid Scripture paraphrases (the OT seen through Christian eyes, as in Watts). He lightly revised Cosin’s BCP version of the Veni Creator (see notes on 522) and his ‘Eucharistic’ verses use that adjective in its authentic sense of ‘thanksgiving’ rather than ‘sacramental’.

Reformed hymn-books naturally include more of his hymns than others; Strict Baptists often have a generous share, such as Denham’s 1837 Selection with at least 40 (second only to Newton among CofE contributors). Spurgeon chose 32 of his hymns for Our Own Hymn Book (1866).

But even some who resist his strong doctrines have acknowledged the merit of his writing. Thus while CH has 11 of his hymns and GH 9, Congregational Praise and its successor Rejoice and Sing both find room for 4—three more than A&M, Songs of Praise etc! As in his lifetime, so now, and as with Jn Wesley, it seems hard to arrive at a balanced view of the man and his writing; some hymn-book companions and most Methodist works are hostile, Dr A B Grosart (in Julian) is lukewarm, while other would-be assessors are plainly ignorant. George Ella’s biography (2000) is now essential reading; see also George Lawton, Within the Rock of Ages, 1983, of which Ella is sharply critical. While both are sympathetic, these evangelical biographers have contrasting assessments from AMT’s boyhood onwards. See also Paul E G Cook (the 1978 Evangelical Library Lecture) as well as earlier works. In 1825 Montgomery recognised an ‘ethereal spirit’ in his writing, calling his poetic touch vivid and sparkling; ‘the writer seems absorbed in the full triumph of faith’. One difficulty is that in the 18th and 19th cents, his name became attached to several hymns from other hands; it is among the strangest of some odd omissions from the 2003 Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals which lists more than 400 others. Nos.705, 711*, 738, 773, 774, 790.