According to your gracious word

- Matthew 26:36-46

- Mark 14:32-42

- Luke 22:39-46

- Luke 23:42

- John 6:31-33

- 641

According to your gracious word,

because you died for me,

I will remember you, my Lord,

in meek humility.

2. Your body, broken for my sake,

my bread from heaven shall be;

I will remember you, and take

this cup you gave for me.

3. Can I Gethsemane forget?

or your fierce conflict see,

and not remember there your sweat

in blood and agony?

4. And when I look upon your blood

once shed on Calvary,

I will remember, Lamb of God,

your sacrifice for me.

5. Yes, while a breath, a pulse remains,

this is my only plea;

I will remember all your pains,

which made me whole and free.

6. And when these failing lips grow dumb

and mind and memory flee,

when you shall in your kingdom come,

Jesus, remember me.

James Montgomery 1771-1854

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

Tune

-

St Fulbert

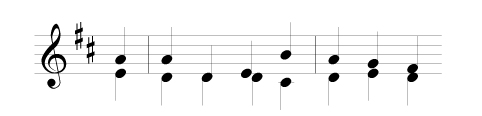

Metre: - CM (Common Metre: 86 86)

Composer: - Gauntlett, Henry John

The story behind the hymn

As the stzs of 638 among others are built upon their identical 1st lines, so James Montgomery’s hymn for the Lord’s Supper is constructed on its similar 4th lines. It was headed with Luke 22:19 on its appearance in his 1825 Christian Psalmist; it featured in his Original Hymns of 1853, and has since found a place in hymnals spanning most denominational and other divides. Like 432 it presents a crux to editors committed to the principles outlined in ‘About Praise!’ Since all stzs except the last end with ‘thee’, an archaic pronoun which the book is committed to removing, the hard choice lies between ending 5 stzs with the less happy ‘… remember you’, and retaining the familiar vowel sound but finding new ways of ending each stz. Either way requires changes to each 2nd line. After much heart-searching and examining drafts of the contrasting approaches, the editors opted for the latter.

Consequent adjustments come in stz 1, from ‘in meek humility [moved to line 4] … I will remember thee [to line 3]’; 2, ‘thy testamental cup I take,/ and thus remember thee’; 3, ‘thine agony and bloody sweat,/ and not remember thee’; 4, ‘O Lamb of God, my Sacrifice!/ I must remember thee’; and 5, ‘Remember thee, and all thy pains [to line 3],/ and all thy love to me:/ yes, while a breath, a pulse, remains [to line 1]/ will I …’ Although in note form this may seem radical, a close comparison of the revised text and that in (eg) CH or GH (which themselves vary at 2.3) will show that the substance of the hymn and most of its detailed phrases, as well as the distinctive sound, has been preserved in what is hoped forms a moving, fresh, intelligible and authentic hymn with its own integrity. As with its original, the word ‘remember’ occurs in every stz. The final occasion, in the last line, quotes the penitent thief in Luke 23:42. The phrase ‘agony and bloody sweat’ in Montgomery’s stz 3, referring to Luke 22:44, is not itself used in Scripture but is taken from Thomas Cranmer’s 1544 (and 1552/1662) Litany, the first-ever public prayers to be authorised in English. In the reforming spirit of Cranmer, this has been adjusted for contemporary users of the language.

Henry J Gauntlett’s straightforward ST FULBERT has been a tune much in demand since its arrival (as ST LEOFRED) in The Church Hymn and Tune Book of 1852, edited by W J Blew and the composer. There it partnered Now Christ our Passover is slain; this seasonal link is retained by the many books following the first A&M in setting it to Ye choirs of new Jerusalem, and adopting its present name. Bishop Fulbert of Chartres (d1028) wrote the Lat original of that hymn.

A look at the author

Montgomery, James

b Irvine, Ayrshire, Scotland 1771, d Sheffield 1854. His father John was converted through the ministry of John Cennick qv. James, the eldest son, was educated first at the Moravian centre at Fulneck nr Leeds, which expelled him in 1787 for wasting time writing poetry. By this time his parents had left England for mission work in the West Indies. In later life he regularly revisited the school; but having run away from a Mirfield bakery apprenticeship, failed to find a publisher in London, and lost both parents, he served in a chandler’s shop at Doncaster before moving to Sheffield, where from 1792 onwards he worked in journalism. Initially a contributor to the Sheffield Register and clerk to its radical editor, he soon became Asst Editor and (in 1796) Editor, changing its name to the Sheffield Iris. Imprisoned twice in York for his political articles, he was condemned by one jury as ‘a wicked, malicious and seditious person who has attempted to stir up discontent among his Majesty’s subjects’. In his 40s he found a renewed Christian commitment through restored links with the Moravians; championed the Bible Society, Sunday schools, overseas missions, the anti-slavery campaign and help for boy chimney-sweeps, refusing to advertise state lotteries which he called ‘a national nuisance’. He later moved from the Wesleyans to St George’s church and supported Thos Cotterill’s campaign to legalise hymns in the CofE. He wrote some 400, in familiar metres, published in Cotterill’s 1819 Selection and his own Songs of Zion, 1822; Christian Psalmist, or Hymns Selected and Original, in 1825—355 texts plus 5 doxologies, with a seminal ‘Introductory Essay’ on hymnology—and Original Hymns for Public, Private and Social Devotion, 1853. 1833 saw the publication of his Royal Institution lectures on Poetry and General Literature.

In the 1825 Essay he comments on many authors, notably commending ‘the piety of Watts, the ardour of Wesley, and the tenderness of Doddridge’. Like many contemporary editors he was not averse to making textual changes in the hymns of others. He produced several books of verse, from juvenilia (aged 10–13) to Prison Amusements from York and The World before the Flood. Asked which poems would last, he said, ‘None, sir, nothing— except perhaps a few of my hymns’. He wrote that he ‘would rather be the anonymous author of a few hymns, which should thus become an imperishable inheritance to the people of God, than bequeath another epic poem to the world’ on a par with Homer, Virgil or Milton. John Ellerton called him ‘our first hymnologist’; many see him as the 19th century’s finest hymn-writer, while Julian regards his earlier work very highly, the later hymns less so. 20 of his texts including Psalm versions are in the 1916 Congregational Hymnary, and 22 in its 1951 successor Congregational Praise; there are 17 in the 1965 Anglican Hymn Book and 26 in CH. In 2004, Alan Gaunt found 64 of them in current books, and drew attention to one not in use: the vivid account of Christ’s suffering and death in The morning dawns upon the place where Jesus spent the night in prayer. See also Peter Masters in Men of Purpose (1980); Bernard Braley in Hymnwriters 3 (1991) and Alan Gaunt in HSB242 (Jan 2005). Nos.152, 197, 198, 350*, 418, 484, 507, 534, 544, 610, 612, 641, 657*, 897, 959.