All creatures of our God and King

- Genesis 1:14-18

- Psalms 104:4-31

- Psalms 147:1

- Psalms 148:2

- Psalms 150:6

- Psalms 52

- Psalms 55:22

- Psalms 65:8-13

- Psalms 84:3

- Matthew 18:35

- Matthew 6:12-15

- Matthew 6:28-29

- Mark 11:25

- Luke 11:4

- Ephesians 4:2-3

- Ephesians 4:32

- Colossians 3:13-14

- 1 Peter 5:7

- Revelation 19:1

- 203

All creatures of our God and king,

lift up your voice and with us sing:

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Bright burning sun with golden beam,

soft shining moon with silver gleam,

O praise him, O praise him,

Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

2. Swift rushing wind so wild and strong,

white clouds that sail in heaven along,

O praise him! Hallelujah!

New rising dawn in praise rejoice,

and lights of evening find a voice;

3. Cool flowing water, pure and clear,

make music for your Lord to hear,

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Fierce fire so masterful and bright,

giving to us both warmth and light,

4. Earth ever fertile, day by day

bring forth your blessings on our way,

O praise him! Hallelujah!

All fruit and crops that richly grow,

all trees and flowers God’s glory show;

5. People and nations, take your part,

love and forgive with all your heart;

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

All who long pain and sorrow bear,

praise God and on him cast your care;

6. Let all things their Creator bless

and worship him in lowliness,

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Praise, praise the Father, praise the Son,

and praise the Spirit, Three-in-One:

In this version Jubilate Hymns† © J. Curwen & Sons LTD

William H Draper (1855-1933),

Based on Francis of Assisi (1182-1226)

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

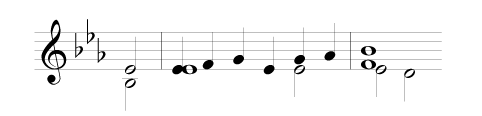

Tune

-

Lasst Uns Erfreuen

Metre: - LM with Hallelujahs

Composer: - Geistliche Kirchengesang

The story behind the hymn

Moving almost unobtrusively from ‘Adoration and thanksgiving’ to the section ‘Creator and sustainer’, we yet again encounter multiple authorship, varied texts, and an expected tune. After the music of an English Psalm 148, here is its distinctive note, first heard in this form to Italian words and latterly with German music. Recent editors have picked their way carefully through the exuberance of Francis of Assisi as mediated 7 centuries later (but hardly 100 years ago) by William Draper. The words form a Christian Benedicite breathing the spirit of that Psalm. ‘Mother earth’ may have once been an acceptable metaphor, but is now open to so many bizarre constructions that it is best avoided. Death is not always ‘most kind and gentle’, still less deserving the title ‘the way to God’; in adapting stz 4, Praise! has followed the Jubilate version’s reluctance to abandon the baby along with the bathwater; in omitting the ‘death’ stz (a final addition when Francis gladly realised he was dying) it has made its own choice, hence the ascription ‘based on …’. Like Jubilate it uses adjectives in stzs 1–3 to replace ‘thou’ and ‘ye’ while preserving the strong rhythm. In 1969 Colin Hodgetts published a modest revision with ‘you’ coming 12 times.The text remains ‘tender as well as grand’—J R Watson. Giovanni Francesco Bernardone (Francis of Assisi) wrote his Cantico di fratre sole (Canticle of the brother Sun, or Song of all Creatures) towards the end of his life, c1225. He dedicated it to one of this brotherhood at a time of great weakness, extreme heat, a plague of mice and virtual blindness; it arose from his meditations on the Psalms in this acute distress. As it stands, it is one of the oldest surviving poems of any kind in Italian. William Draper’s paraphrase starts with the 2nd stz of the Italian and dates from some time between 1906 and 1919, when it appeared in The Public School Hymn Book. It was written for a Whitsuntide festival for children (cf 152 and 198) in the parish of Adel, near Leeds, where the author was rector. Matthew Arnold’s version is closer to the Italian, but has never proved as popular as Draper’s. The 17th-c tune LASST UNS ERFREUEN (=EASTER SONG/HYMN), as arranged here by Ralph Vaughan Williams, was a new arrival in English hymn books when William Draper constructed his text upon it; see the notes to 171.

A look at the authors

Draper, William Henry

b Kenilworth, Warwicks 1855; d Clifton, Bristol 1933. Cheltenham Coll and Keble Coll Oxford; ordained (CofE) 1880. Curate and later vicar in Shrewsbury, also serving the parishes of Alfreton, Derbys, and (for 20 years) Adel, Leeds; he was then Master of the Temple, London, 1919–30. He translated from the Italian of Petrarch and more than 60 Lat and Gk hymns, wrote many original texts, and edited or compiled several hymn collections between 1897 (The Victoria Book of Hymns) and 1925 (Hymns for Tunes by Orlando Gibbons). In 1919 he edited Seven Spiritual Songs by Thomas Campion (1567–1620). Many of his own texts appeared first in church periodicals; he is known today mainly for one of them, his paraphrase of Francis of Assisi’s ‘Canticle of the Sun’. No.203.

Francis of Assisi (Bernardone, Giovanni Franceso)

b Assisi, central Italy, 1182; d Assisi 1226. Brought up in comparative luxury, he pursued pleasure as a youth but at 20 was imprisoned during a local war. Serious illness made him rethink his lifestyle, but by 1205 several factors had combined to change his life. A vision at Spoleto interrupted his further military plans; back at Assisi he met a man suffering from leprosy; and reported hearing a voice from the cross in the ruined church of San Damiano, telling him to rebuild it, which he did with the help of friends and adherents. He left his family, vowed lifelong poverty, and began a ministry to poor and sick people which included a pilgrimage to Rome, 1207. In 1209 he drew up a simple rule for his ‘brothers’, sending them to preach, work, beg, and always be joyful—founding what became the rapidly-growing Franciscan order. In at least one notable sermon, and perhaps others, he addressed ‘Angels, men, and demons…’. Plans for a mission to Syrian Muslims were thwarted by shipwreck and illness, and after healing rifts among his followers but failing to halt what he saw as worldly compromises he eventually withdrew from formal religious activity, retaining only his love of the natural world and its wild creatures. His life of prayer, meditation and singing was marked by increased pain and blindness, notably in his final 2 years. Part of that time he spent in a small solitary hut, but not finding any cure, he was carried back to Assisi to die. In spite of his many troubles, such joy kept breaking through that he was dubbed ‘joculator Dei’—God’s joker. Francis’s first (and second) biographer, in rhythmical Lat prose, was his younger friend and follower Thomas of Celano (c1190–1260) who may also have written hymns and produced two ‘lives’ in 1228 and 1246–47, both at the insistence of other friends. It must be regretted that in the Roman veneration of such a remarkable man, some of the historic and human facts have been overlaid with pious legend. No.203.