Behold the glories of the Lamb

- Exodus 19:6

- Psalms 146:7

- Psalms 33:3

- Psalms 96:1

- Psalms 98:1

- Matthew 24:22-24

- Matthew 24:36

- Matthew 24:42-44

- Matthew 25:13

- Mark 13:20

- Mark 13:32

- Luke 12:40

- Luke 4:18

- John 1:29

- Ephesians 1:7

- Hebrews 11:10

- Hebrews 2:9

- 1 Peter 1:18-19

- 1 Peter 2:9

- Revelation 1:18

- Revelation 1:5-6

- Revelation 22:5

- Revelation 5:12

- Revelation 8:3-4

- 486

Behold the glories of the lamb

upon his Father’s throne;

prepare new honours for his name

and songs before unknown!

2. Let elders worship at his feet,

the church adore around,

with golden bowls of incense sweet

and harps of sweeter sound.

3. Those are the prayers of all the saints

and these the hymns they raise;

Jesus is kind to our complaints

and loves to hear our praise.

4. Eternal Father, who shall look

into your secret will?

Who but the Son can take that book

and open every seal?

5. He shall fulfil your great decrees;

the Son deserves it well;

see in his hand the sovereign keys

of heaven, and death, and hell!

6. Now to the Lamb who once was slain

be endless blessings paid;

salvation, glory, joy remain

the crown upon your head.

7. You have redeemed our souls with blood

and set the prisoners free;

you made us kings and priests to God

to reign eternally.

8. The worlds of nature and of grace

are put beneath your power;

then shorten these delaying days

and bring the promised hour!

Isaac Watts 1674-1748

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

Tune

-

St Saviour

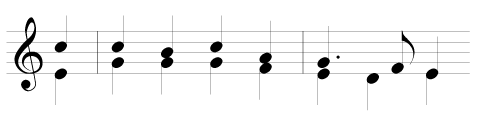

Metre: - CM (Common Metre: 86 86)

Composer: - Baker, Frederick George

The story behind the hymn

‘New honours … songs before unknown’: such are the clues in the opening lines that these stzs are the doorway into English hymnody as we know it. For this is the first hymn to come from the pen of the young Isaac Watts, c1696, after he complained to Isaac senior about the poor fare on offer for the congregation at Southampton’s Above Bar (Independent) Church. His father, who by now had some notion of his son’s talent, famously suggested that he should try to do better. So he did. The hymn based on Revelation 5 but not limited to it was apparently sung at the church within days, and proved acceptable enough for hundreds more to follow. Many later features of Watts’ writing are seen in embryo here; we notice among much else the blood of Christ, the freed prisoners, and the worlds of nature and grace. Routley goes so far as to say that ‘In it is the germ of all the 700-odd pieces he subsequently wrote’. But the opening line stands as an archway above the door with ‘glories’ as the keystone at its head, and ‘Behold’ repeating the word by which John the Baptist first introduces us to the Lamb of God (John 1:29). 3 stanzas are addressed to fellow-worshippers; stz 4 turns to address God the Father, and 6 is a further turning-point, ‘Now to the Lamb …’. Having begun a kind of doxology, we then address Christ directly, and end with a strong prayer which relates the scriptural imagery to today’s urgent needs. See also E Routley, A Panorama of English Hymnody (1979) pp16ff; J R Watson, The English Hymn (1997), pp137ff; and C Idle in HSB223 (April 2000). The startling fact is how few hymnals see fit to include this epoch-making text; among them are Christian Worship (1976) with a curiously mixed version, and collections from Scotland and Ireland.

To return to the text: it is no. 1 in Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1707), Bk 1, ‘Collected from the [Holy] Scriptures’ where it is headed ‘A New Song to the Lamb that was slain. Revelation 5:6,8,9,10,12.’ Watts returned many times to this chapter. It has needed only minor changes from the original, which had ‘amidst’ (1.2), ‘vials full of odours’ (2.3), ‘shall’ (4.3), ‘Lo’ (5.3), ‘for ever’ (6.4), ‘and we shall reign with thee’ (7.4).

The tune ST SAVIOUR here makes the second of its 3 appearances in Praise!; see 214, 509. It is also in demand for the words of 969 and 974; it is tempting to postulate a musical affinity with the mood and movement of Watts’ verse.

A look at the author

Watts, Isaac

b Southampton 1674, d Stoke Newington, Middx 1748. King Edward VI Grammar Sch, Southampton, and private tuition; he showed outstanding early promise as a linguist and writer of verse. He belonged to the Above Bar Independent Chapel, Southampton, where his father was a leading member and consequently endured persecution and prison for illegal ‘Dissent’. Some of the historic local landmarks in the family history, however, have question-marks over their precise location. But for Isaac junior’s undoubted first hymnwriting, see no.486 and note; the Psalm paraphrases then in use often were, or resembled, the Sternhold and Hopkins ‘Old Version’, described by Thos Campbell as written ‘with the best intentions and the worst taste’, or possibly the similarly laboured versions of Thomas Barton. His solitary marriage proposal to the gifted Elizabeth Singer was not the only one she rejected, but they remained friends, and her own hymns (as ‘Mrs Rowe’) were highly praised and remained in print until at least around 1900. After further study at home, in the year after Horae Lyricae (published 1705) and at the age of 32, Watts became Pastor of the renowned Mark Lane Chapel in the City of London and private tutor/chaplain to the Abney family at Theobalds (Herts) and Stoke Newington. Chronic ill health prevented him from enjoying a more extensive or prolonged London ministry, though with the care of a loving household he lived to be 74.

In 1707 came the 3 books of Hymns and Spiritual Songs, and in 1719, The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament, and Applied to the Christian State and Worship. As he is acknowledged as the father of the English hymn, so he became the pioneer of metrical Psalms with a Christian perspective. He is acknowledged as such by Robin Leaver who once added, a touch prematurely, that he was equally the assassin of the English metrical Psalm! His own ‘design’ was ‘to accommodate the Book of Psalms to Christian Worship…It is necessary to divest David and Asaph, etc, of every other character but that of a Psalmist and a Saint, and to make them always speak the common sense of a Christian’. His ‘Author’s Preface’ from which this is taken is a brief apologia for his aim and method; he desires to serve all ‘sincere Christians’ rather than any one church party, and he explains the careful omissions and interpretations of hard places. Above all, he is ‘fully satisfied, that more honour is done to our blessed Saviour, by speaking his name, his graces and actions, in our own language…than by going back again to the Jewish forms of worship, and the language of types and figures.’

Not always accepted by his contemporaries, he nevertheless laid the foundations on which Charles Wesley and others built. Some of his hymns and Psalm versions are among the finest in the language and still in worldwide use; Congregational Praise (1951) has 48 of his hymns, and CH (2004 edn), 59. Many of these are found in the early sections of a thematically-arranged hymn-book, under ‘God the Father and Creator’ or similar category.

With his best-selling Divine Songs attempted in Easy Language, for the sake of Children (1715) he was the most popular children’s author in his day (and well into the 19th c); those who understandably recoil today at some of them would do well to see what else was on offer, even 100 or more years later. Watts, too, was a respected poet, preacher and author of many doctrinal prose works. He corresponded as regularly as conditions then allowed with the leaders of the remarkable work in New England. A tantalisingly brief reference in John Wesley’s Journal for 4 Oct 1738 (neither repeated nor paralleled, and less than 5 months after JW’s ‘Aldersgate experience’), reads: ‘1.30 at Dr Watts’. conversed; 2.30 walked, singing, conversed…’. Dr Samuel Johnson and J Wesley used his work extensively, the former including many quotations from Watts in his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language. His work on Logic became a textbook in the universities from which he was barred because of his nonconformity. The current Oxford Book of English Verse (1999) includes 5 items by IW including his 2 best-known hymns. Further details are found in biographies by Arthur P Davis (1943), David Fountain (1974) and others, the 1974 Annual Lecture of the Evangelical Library by S M Houghton, and publications of the British and N American Hymn Societies (by Norman Hope, 1947) and the Congregational Library Annual Lecture (by Alan Argent, 1999). See also Montgomery’s 4 pages in his 1825 ‘Introductory Essay’ in The Christian Psalmist, where he calls Watts ‘the greatest name among hymnwriters…[ who] may almost be called the inventor of hymns in our language’; and the final chapter of Gordon Rupp’s Six Makers of English Religion (1957). The 1951 Congregational Praise is rare among hymn-books for including more texts by Watts than by C Wesley. Nos.5*, 122, 124, 136, 146, 163, 164, 171, 189, 208, 214, 231, 232, 241, 255, 260, 264, 265, 300, 312, 363, 401, 411, 453, 486, 491, 505, 520, 549, 557, 560, 580, 633, 653, 692, 709*, 780, 783, 792, 794, 807, 969, 974*, 975.