By gracious powers so wonderfully sheltered

- Psalms 119:71

- Psalms 75:7-8

- Psalms 9:11

- Lamentations 3:22-23

- Matthew 20:22-23

- Matthew 28:20

- Mark 10:38-39

- John 16:33

- Romans 12:1

- Romans 8:18

- Ephesians 5:16

- James 1:21-22

- 1 Peter 1:9

- Revelation 12:9

- 236

By gracious powers so wonderfully sheltered

and confidently waiting, come what may,

we know that God is with us night and morning,

and never fails to meet us each new day.

2. Yet are our hearts by their old foe tormented;

still evil days bring burdens hard to bear;

O give our frightened souls the sure salvation

for which, O Lord, you taught us to prepare.

3. And when the cup you give is filled to brimming

with bitter suffering, hard to understand,

we take it gladly, trusting though with trembling,

out of so good and so beloved a hand.

4. If once again, in this mixed world, you give us

the joy we had, the brightness of your sun,

we shall recall what we have learned through

sorrow,

and dedicate our lives to you alone.

5. Now as your silence deeply spreads around us,

open our ears to hear your children raise

from all the world, from every nation round us,

to you their universal hymn of praise.

English versification © Stainer & Bell Ltd. Adapted by permission of SCM Press from Bonhoeffer's 'Powers of Good', letters and papers from prision 1971

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-45)

Trans. Fred Pratt Green and Keith Clements

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

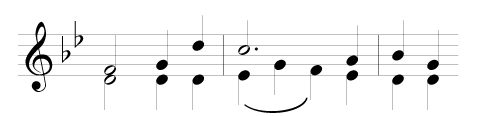

Tune

-

Highwood

Metre: - 11 10 11 10

Composer: - Terry, Richard Runciman

The story behind the hymn

Dietrich Bonhoeffer was a pastor of the Confessing (Evangelical) Church in Germany which in the 1940s stood firm against the racist and genocidal Nazi policies of Adolf Hitler. Having been implicated in a plot to assassinate him, Bonhoeffer was arrested in 1943, imprisoned, and eventually hanged in April 1945, weeks before Hitler’s own death and the end of the war. One of his last letters smuggled out of the Gestapo bunker-prison in Prinz- Albrecht-Strasse, Berlin, was a New Year greeting to his parents, with which he enclosed the hymn text. The original 7 stzs of German are very stark; this translation made by Fred Pratt Green retains the note of triumph through torment, while also rendering it as a congregational hymn. It is available in varied versions; FPG wrote his in 1972, as printed in Cantate Domino (1974 and 1980). The first 3 stzs are virtually those printed in The Hymns and Ballads of Fred Pratt Green (1982); he put the original final one first: Von guten Machten wunderbar geborgen. Stz 4 shows some variation, while 5 (by Keith Clements?) is a later adaptation of stz 6 in the German. More details are included in the Companion to Rejoice and Sing (1999), pp590–592.

Josef Gelineau was the first to set Bonhoeffer’s text to music; the translation here has been used with Parry’s tune INTERCESSOR (12) or, as here, with Richard Terry’s exhilarating HIGHWOOD, repeated at 620. This was written, at the suggestion of the composer’s uncle Lord Runciman, for O perfect love, but first appeared in the 1933 Methodist Hymn Book paired with FWH Myers’ Hark, what a sound. It has been described as Terry’s finest tune, and well conveys the buoyancy of faith maintained through some extremes of testing.

A look at the authors

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich

b Breslau, Germany 1906, d Flossenburg, Germany 1945. Tutored initially at home by the Moravian Fräulein Horn who loved hymns; his mother taught him Scripture, and his father was a teaching consultant and Germany’s first Prof of Psychiatry, who hated platitudes, gossip and pomposity. Dietrich remained close to his twin sister Sabine, in a household (now moved to Berlin) well supplied with books, music, animals and a workshop, with due time for sport. He studied atTübingen from 1923, and after travels to Rome and N Africa he resumed theology at Berlin (Licentiate of Theol/PhD, 1927). After serving briefly as curate in Barcelona in 1928 he was an assistant minister in Berlin, 1929–30. In 1930 he became an accredited university teacher, lecturing in theology from 1931, the year of his ordination, after further studies at the Union Theological Seminary in New York and with Karl Barth in Bonn. His written and spoken contributions to conferences etc included papers on the church, creation and sin, Christology, and the Jewish people. He cooperated with Martin Niemoller for the Pastors’ Emergency League in the face of rising Nazism, becoming the spokesman for internal protestant opposition to the regime. In 1933–34 he ministered in London for 18 months and first met Bishop George Bell of Chichester, who became a staunch friend and ally. Back in Germany he lectured on ‘discipleship’ (1936); The Cost of Discipleship was published the next year, the last book to emerge in his lifetime and which he later qualified but never contradicted; recent appreciation of this book has come from Charles Colson, Stormie Omartian and Ron Sider among many others.

In 1941 DB’s works were proscribed by Nazi Germany. But before that his licence to lecture had been revoked for his opposition to Adolf Hitler, colleagues and students were being arrested and the preachers’ seminary closed. Life Together was written in 1938, reflecting his leadership of the seminary at Finkenwalde 1935–37; in 1939 he again met significant friends in London and New York, but realised that his true place was in Germany, alongside his own people. By 1940 he was forbidden to speak in public and ordered to report to the police. He travelled to Switzerland 1941–42, became engaged to Maria in 1942, but in April 1943 was arrested and imprisoned. In 1944 came the attempt to assassinate Hitler in which Bonhoeffer and his sister and brother-in-law were implicated; he was taken to the cellar of the Gestapo (secret police) prison in Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse. In 1945 he was moved via Buchenwald concentration camp and Regensburg to the extermination centre at Flossenburg, while Nazi rule was collapsing. There he was court-martialled the same night and hanged the next morning (9 April), on Himmler’s orders, only weeks before Hitler’s death and the end of the war. He was 39. Much of his fame beyond Germany was osthumous and delayed, including the published Letters and Papers from Prison and Christology (in German 1960; in English, 1966 and 1978); some of his books remained unfinished and some were reconstructed from his students’ notes.

While he distinguished religion from real faith, his Luther-like paradoxes have often been sadly misinterpreted or hijacked by those who ignore his devotion to Scripture and disciplined evangelical foundations; he did not feature in the 1958 edn of the (then definitive) Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, but many more recent books have tried both to correct and complete the record. Neither his friends nor his foes should see him through the 1960s eyes of John A T Robinson. The solution to ethical problems, Bonhoeffer consistently taught, ‘must be sought only in the revelation of God in Christ’. This is the Christological question: ‘When I know who he is, who does this, I will know what it is he does’. Among his recreations he loved to improvise on the piano and found bad music unbearable; hymns should be ‘not too slow’. He has been called ‘a most unGerman German’, full of vitality and excelling in many gifts, combining some of the expected national characteristics with a playful sense of fun. He enjoyed life. I knew Dietrich Bonhoeffer (ed W-D Zimmerman and R Gregor Smith, 1966) fills in much of the personal picture; among many recent studies of his place in history is one by Stephen Haynes in 2004. No.236.

Green, Fred Pratt

b Roby nr Liverpool 1903, d Norwich, Norfolk 2000. Huyton High Sch, Wallasey Grammar Sch, and Rydal Sch, Colwyn Bay. Attending Childwall Parish Ch (his mother’s church) as a child he became aware of Hymns A&M. The family moved to Wallasey where they joined the Wesleyans (his father’s first spiritual home) and Fred remembered singing lots of hymns, many of them long. A friendship with his fellow-pupil Eric Thomas, a future Anglican vicar, began with a satchel fight but blossomed as they attended each other’s churches on alternate Sunday evenings. The nonconformists’ open invitation to Communion strengthened Fred’s Methodist convictions, while the English master A G Watt sparked Fred’s lifelong love of poetry. Attracted once to an architect’s career, he was deeply moved by an address at Wallasey on John Masefield’s The Everlasting Mercy; he offered for the Methodist ministry, seeing his first work in print (a play) while in training at Didsbury Theological Coll, Manchester (1925–28). He was ordained in 1928. Dissuaded by the Principal from his desire to work in Africa, he was urged instead to become chaplain at the new Methodist girls’ boarding sch at Hunmanby, Yorks. While there he married Marjorie Dowsett who taught French, and served in the Filey Methodist circuit. He then moved to Girlington nr Bradford, followed in 1939 by Gants Hill nr Ilford, Essex. Then at Finsbury Park (1944–47) he met Fallon Webb— agnostic, invalid, and poet; for 20 years they continued to meet to share and gently criticise each other’s work. His next posting was to the Dome Mission at Brighton, where Fred preached to 2000 or more on Sunday evenings; then in 1952 to Shirley nr Croydon, and in 1957 to York. His final pastorate (1964) was one of his happiest, at Sutton Trinity not far from Shirley. He had by now published several poems, and became more widely known by his 1963 collection The Skating Parson, and a single poem The Old Couple in the BBC weekly The Listener a year later.

But a more significant step was his appointment in 1967 to a group preparing a supplement to the Methodist Hymn Book, eventually emerging as Hymns and Songs (1969). It was John Wilson, formerly of Charterhouse Sch, then at RCM, who encouraged Fred not just to assess other verse but to contribute his own. So began, in his mid-60s, virtually a new career which led to his being acclaimed as the finest Methodist hymn-writer since the Wesleys—who of course were Anglicans! 27 of the 177 texts in Partners in Praise (1979) were FPG’s; and when the Methodists revised their main book as Hymns and Psalms (1983) 27 of his texts were again included. The American The United Methodist Hymnal (1989) had 18, more than any other living writer. Hundreds of hymnals worldwide (especially in the UK and USA) now feature his work, which has been sung at several national events in Britain. His own main collections are The Hymns and Ballads of Fred Pratt Green (1982); Later Hymns and Ballads and Fifty Poems (1989); and the posthumous Serving God and God’s creatures (a memorial volume, 2001) and Partners in Creation (2003). He wrote some 300 hymns, including one officially chosen for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee in 1977, It is God who holds the nations. Among others most widely acclaimed are In praise of God meet duty and delight and To mock your reign, O dearest Lord. The notes in all these volumes also make FPG the most fully-annotated of 20th-c hymn-writers, thanks largely to his friend and editor Bernard Braley whose own Hymnwriters 3 (1991) contains further biography. Fred retired to a Methodist Home in Norwich in 1990, and in 1991 published his final book of verse, The Last Lap, still marked by faith, skill and gentle humour; Marjorie Green died in 1993. Throughout his life he struggled with the changing face of theology, with both intellectual problems and social needs, preaching and writing, as he put it, ‘in an age of change and doubt’. He interacted with writers, musicians and church leaders on both sides of the Atlantic, and his writing royalties over many years were channelled into a Trust which still contributes to many hymn-related causes and helped to establish the Pratt Green Library housed in the Univ of Durham. Erik Routley wrote of FPG in 1979 that ‘no hymnal that ignores him can claim to be fully literate’. Carlton Young speaks of his ‘unique and immense contribution to the writing of hymns and the editing and compilation of hymnals’. Nos.236*, 288, 431, 696, 899, 906, 916, 930.