Christ Jesus lay in death's strong bands

- Numbers 9:1-14

- Psalms 149:1

- Malachi 4:2

- John 15:11

- John 6:32-35

- John 6:50-58

- Acts 14:3

- Acts 20:32

- Acts 7:55-56

- Romans 13:11-14

- Romans 4:25

- Romans 5:12-21

- 1 Corinthians 15:26

- 1 Corinthians 15:3-4

- 1 Corinthians 15:55-57

- 1 Corinthians 5:6-8

- 2 Timothy 1:10

- Hebrews 2:14-15

- Hebrews 3:1

- Revelation 1:16

- 456

Christ Jesus lay in death’s strong bands

for our offences given;

but now at God’s right hand he stands,

and brings us life from heaven:

let us give thanks and joyful be,

and to our God sing faithfully

loud songs of hallelujah!

2. It was a strange and dreadful strife,

when life and death contended;

the victory was gained for life,

the reign of death was ended:

stripped of its power, no more it reigns:

an empty form alone remains;

its sting is lost for ever.

3. Let us obey his heavenly call

by which the Lord invites us;

Christ is himself the joy of all,

the sun who warms and lights us;

in love and mercy he imparts

eternal sunshine to our hearts;

the night of sin is ended.

4. Let us his people feast this day

upon the bread of heaven.

The word of grace has purged away

the old, corrupting leaven;

now Christ alone our souls will feed,

he is our meat and drink indeed,

faith lives upon no other.

Martin Luther 1483-1546 Trans. Richard Massie 1800-87

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

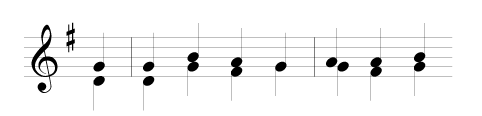

Tune

-

Luther's Hymn

Metre: - 87 87 887

Composer: - Geistliche Lieder (1535)

The story behind the hymn

Like 455, this translation from Martin Luther is surprisingly neglected by many hymnals. This too is a highly-acclaimed text, attracting praise from Julian and many others. It has pride of place as no.1 in Erik Routley’s A Panorama of Christian Hymnody (1979), where he points to the ‘spiritual drama’ it presents. The German Christ lag in Todesbanden first appeared in 1524 as a hymn of 84 lines. But Luther was himself drawing partly on Michael Weisse (see 457) and even more on the 11th-c Lat sequence ascribed to Wipo of Burgundy, Victimae Paschale laudes. Richard Massie translated the German text for his Martin Luther’s Spiritual Songs (1854), and in the same year it appeared in William Mercer’s The Church Psalter and Hymn Book. The text shows several variations in different current hymnals. Stz 1 of Massie’s version has ‘… light from heaven … and sing to God right thankfully’; 3, ‘So let us keep the festival/ whereto … by his grace he doth impart’; 4, ‘Then let us feast this Easter day/ on the true Bread of heaven./ The word of grace hath purged away/ the old and wicked leaven’. Echoes of Acts 7:55–56 and 1 Corinthians 5:7–8 remain.

For notes on the tune LUTHER’S HYMN see 29; it also appears at 962. The words are set in the earlier books and several current ones to another Lutheran adaptation, CHRIST LAG IN TODESBANDEN.

A look at the authors

Luther, Martin

b Eisleben, Saxony (Thuringia) 1483, d Eisleben 1546. Latin schools at Magdeburg and Eisenach; Univ of Erfurt (bachelor’s and master’s degrees 1502, 1505); he then took up the study of law. A summer thunderstorm in 1505, in which he called on St Ann for help, led him against family and friends’ advice to fulfil a vow made in fear and become a monk. He was admitted to the Observant Augustinian Friars in Erfurt and at first was a model ‘religious’. But all his outward observances gave him no peace of mind and he longed to know the God of grace, not just his terrible power. Ordained in 1507, he nearly fainted at the awesomeness of his first mass; even more troubled by his conscience, he was advised by Johann von Staupitz simply to love God. ‘But I hate him!’ said ML. Long study of the Bible led him to dwell on the Pss and the phrase ‘the righteousness of God’ in Rom 1:17. But he struggled to find its meaning; eventually, and possibly alone in his monastery tower, he realised that this was secured by Christ, and that he was justified by faith alone. This, he said, was like a new birth, and took place somewhere between 1512 and 1519. Meanwhile he had lectured on the standard medieval textbooks, completed his doctorate, and succeeded Staupitz as Bible lecturer in the Univ of Wittenberg. His lectures on Psalms (twice), Rom, Gal and Heb (1513–19) led him increasingly to question the theory and practice of the RC church: ‘In the course of this teaching the papacy slipped away from me’—ML. In Oct 1517 he posted 95 ‘theses’ for debate on the door of Wittenberg’s Castle Ch, beginning with the suggested replacement of ‘penance’ with a life-changing and lifetime repentance, and implicitly undermining the ‘indulgence’ industry promoted by the Dominican monk Johann Tetzel which promised forgiveness for cash. The theses made Luther a figure of major controversy. Cardinal Cajetan was sent by the pope to correct Luther, who clarified and expanded his views at the 1518 Heidelberg Disputation, winning over Martin Bucer in the process. In 1519 he likewise confronted John Eck at Leipzig, enunciating the ‘sola Scriptura’ (Bible only) slogan, quoting the protestant martyr John Hus with approval, and denying the infallibility of church pronouncements and the primacy of the pope. In 1520 he wrote 3 major works, An Appeal to the Nobility, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and The Freedom of a Christian Man. He was excommunicated but publicly burned the relevant document (or ‘bull’) and a volume of canon law. Then at the 1521 Diet of Worms he was required to retract, a demand producing his watchword: ‘My conscience is captive to the word of God…Here I stand, I can do no other; so help me, God, Amen’.

Luther was then virtually hidden in the Wartburg Castle nr Eisenach by the friendly Elector, prince Frederick III. There he translated the NT into German (1522); his OT appeared in 1534, and together they became for German-speakers what the 1611 AV was soon to be for English ones. In 1525 The Bondage of the Will was Luther’s classic reply to the liberal reformer Erasmus. That year also saw the radical breakaway from Luther by the violent Thomas Müntzer; more happily, ML’s marriage to the runaway nun Catherine de Bora gave him a more balanced way of life, and a Wittenberg household full of both children and student boarders. The Reformation prospered through his numerous sermons, letters, commentaries (notably favouring Galatians which he dubbed ‘my Katie!’) and some 37 hymns; even his eagerly noted table-talk. His later years, beset by many health problems, also produced more aggressive polemics against the pope; and even against his fellow-reformer Ulrich Zwingli and against the Jewish people. Of a great many biographies, Roland Bainton’s Here I stand (reprinted 1990) became a 20th-c classic; of a selection of 21st-c Christian writers asked which books had influenced them most, several mentioned one or another of Luther’s works; see Indelible Ink, ed Scott Larsen 2003.

ML was a skilled musician, and although his use of congregational singing was not new (Hus and his followers sang hymns), he developed vernacular hymnody, with doctrinal and intelligible words sung to user-friendly tunes, as none had done before him and no major Reformation figure did afterwards. His influence on English hymnody, however, was delayed until the 18th c since these islands had taken a more Calvinist path, as reinterpreted by Watts and his followers. British enthusiasm for Luther as a hymnwriter probably reached its peak in the 19th c, with many fine translators, notably women, providing the way in to his texts: see especially the notes on Borthwick, Cox, Massie and Winkworth. While some of Luther’s distinctive (even wayward) views on the canon of Scripture and on sacramental and social issues remain problematic, his crucial role in clarifying justification by faith (‘the article of a standing church’) remain pivotal for all Protestant Christians. So does his pioneering work for intelligible, intelligent and Christ-centred hymn-singing. Nos.456, 888. 29*?, 750*.

Massie, Richard

b Chester, Ches 1800, d Pulford Hall, Coddington, nr Chester 1887. The son of a clerical family, he inherited two large ancestral estates and spent most of his time in (and on) his garden and with his books. He published a translation of Martin Luther’s Spiritual Songs (1854) and Lyra Domestica (translated from Karl Spitta qv, 1860) and contributed English versions of other German texts to various hymn-books and journals including Wm Mercer’s Church Psalter and Hymn Book (1854, once very popular) and Reid’s British Herald. 13 of these are versions from P Gerhardt; one is his much-reprinted translation of Ein’ feste Burg (see 888, note) which, however, has had to face stiff competition. As with the hymn included here, and his version of Luther’s paraphrase of Ps 130 beginning. ‘From depths of woe I raise to thee/ the voice of lamentation’, Massie ‘often achieves an eloquence which translators usually find it necessary to renounce’— Routley. He is represented by at least one hymn in several current books, mainly those from the Free Churches. No.456.