Christ, the Lord, is risen today

- Psalms 24:7-10

- Psalms 69:34

- Psalms 96:11

- Isaiah 44:23

- Isaiah 49:13

- Hosea 13:14

- Malachi 4:2

- Matthew 16:18

- Matthew 27:59-66

- Matthew 28:1-10

- Matthew 28:6

- Mark 15:46

- Mark 16:1-8

- Luke 23:43

- Luke 23:45

- Luke 24:1-9

- Luke 24:34

- Luke 24:6

- John 19:30

- John 20:1-10

- Acts 2:33

- Acts 2:36

- Acts 5:31

- Romans 6:4-6

- Romans 6:8-10

- 1 Corinthians 15:55-57

- 2 Corinthians 4:10

- 2 Corinthians 4:14

- Ephesians 1:22

- Ephesians 1:3-14

- Philippians 2:10

- Colossians 1:18

- Colossians 3:1-2

- 1 Timothy 2:11

- James 1:21-22

- 1 Peter 1:9

- 1 John 3:2

- Revelation 2:7

- 458

‘Christ, the Lord, is risen today!’

Hallelujah!

All creation join to say:

Hallelujah!

Raise your joys and triumphs high;

Hallelujah!

Sing, you heavens, and earth reply:

Hallelujah!

2. Love’s redeeming work is done!

Fought the fight, the battle won:

see, our Sun’s eclipse has passed;

see, the light returns at last!

3. Vain the stone, the watch, the seal:

Christ has burst the gates of hell;

death in vain forbids him rise-

Christ has opened paradise:

4. Lives again our glorious King;

where, O death, is now your sting?

Once he died, our souls to save;

where’s your victory, boasting grave?

5. Soar we now where Christ has led,

following our exalted Head;

made like him, like him we rise;

ours the cross, the grave, the skies:

6. Hail the Lord of earth and heaven!

Praise to you by both be given;

every knee to you shall bow,

risen Christ, triumphant now!

© In this version Jubilate Hymns

This is an unaltered JUBILATE text.

Other JUBILATE texts can be found at www.jubilate.co.uk

Charles Wesley 1707-88

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

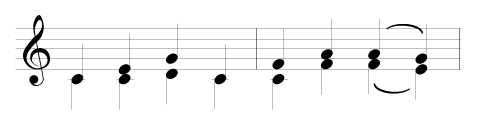

Tunes

-

Easter Hymn

Metre: - 77 77 with hallelujahs

Composer: - Lyra Davidica (1708)

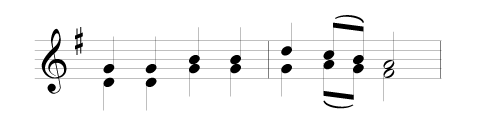

-

Llanfair

Metre: - 77 77 with hallelujahs

Composer: - Williams, Robert

The story behind the hymn

The second of the resurrection trio (see note to 457) is Charles Wesley’s best-known Easter text, which has sometimes squeezed one or both of the others out of the hymn-book. Martin Madan made an early adaptation in 1760; Methodists have understandably given it pride of place, but only since the 1831 Supplement to their book, while Anglicans have often started at stz 2. It first appeared as a ‘Hymn for Easter Day’ in the 1739 collection Hymns and Sacred Poems; the Companion to Hymns and Psalms (1988) sees it as ‘modelled on’ the anonymous 470, and adds that ‘In the various versions of this great hymn there are many alterations and additions’. The original had 11 stzs; 6 is an average length today, bearing in mind the repeated Hallelujahs which have the effect of making it a 48-line hymn, in the singing if not on the page. Many hymnals conclude with the final stz printed here, but have ‘Thee we greet triumphant now;/ hail, the resurrection thou!’ The changes here are largely those adopted by HTC, except for 4.1–2, 5.1, and the beginning where the Jubilate version has ‘All creation join to say [a new line]/ Christ the Lord is risen today’. Wesley’s 2nd line was ‘Sons of men and angels say’. Stz 2 ended ‘… eclipse is o’er; Lo! he sets in blood no more!’ The final line of stz 4, borrowed from the end of a Watts hymn of 1709 (He dies, the Heavenly Lover/Friend of sinners dies), was grafted on to this one in the 1831 book. One omitted stz, sometimes used as the last, is ‘King of glory! Soul of bliss!/ Everlasting life is this;/ thee to know, thy power to prove,/ Thus to sing and thus to love’. PHRW uses this, but ends with ‘… resurrected God of love’.

For notes on the anonymous tune now known as EASTER HYMN, see 470. It was soon seized on by John Wesley for this text by Charles, and presented as the (by modern standards) highly decorative SALISBURY TUNE in the 1742 Foundery Collection. An alternative is LLANFAIR (457) while some traditions follow A&M in using SAVANNAH, with a single Hallelujah concluding each stz.

A look at the author

Wesley, Charles

b Epworth, Lincolnshire 1707, d London 1788. The youngest of 17 children born to Samuel and Susanna, he scarcely survived birth. Somehow he also survived a hugely talented but chronically poor and often dysfunctional family, taught and held together by his mother through multiple disasters. At Westminster Sch he was nurtured by his gifted elder brother Samuel; at Christ Ch Oxford, supported by John W and others in 1728–29, he founded the ‘Holy Club’ which earned the nickname of ‘Methodists’. A fellow-student John Gambold described him as ‘a man made for friendship’; he certainly befriended and encouraged the younger and poorer student George Whitefield. Under pressure from his brother John, Charles was ordained in 1735 (delighting later to call himself ‘Presbyter of the Church of England’) in order to travel with him on a neardisastrous visit to the young colony of Georgia, which however brought the brothers into contact with Moravian missionaries. While putting a positive public spin on his adventures, but partly driven by the Moravian sense of assurance, he experienced an evangelical conversion on 21 May 1738, shortly before John’s more celebrated ‘heart-warming’. Charles’s journal is shorter, rather more transparent and less contrived than his brother’s; he was never a self-propagandist. But in 1964 the historian F C Gill called him ‘the first Methodist’ (from his Oxford initiatives) and ‘the apostle of the north’ (from his labours around Newcastle).

Like John’s inward transformation, Charles’s suffered many setbacks, but his hymnwriting began immediately (see 751, note) and for the next decade he shared in countrywide itinerant evangelism, often opening the way for his brother and composing much verse while on horseback. ‘His sermons and his hymns informed each other’ – David Chapman. In 1749 he married Sarah (Sally) Gwynne, settled in Bristol and unlike John became less relentlessly mobile and more firmly Anglican. But at least until 1757 he still continued to travel, attract audiences in their tens of thousands and oversee the growing army of lay preachers and (like Whitefield) labour for harmony between the movement’s leaders. In that year, however, his journal-keeping ended, and his lifestyle was redirected by concern for his wife (who had contracted smallpox), by his own health problems, and by the widening gap between John and himself. The differences arose from John’s elusive ‘perfectionism’ (from 1760), his increasing willingness to distance himself from the CofE, and his autocratic leadership-style.

By common consent, CW is the greatest of all English hymnwriters and certainly the most prolific, completing more than 6000 over 50 years; the exact number depends on whether some poems or single-stanza texts are included. Some self-contained 4-line items are very powerful, and we may regret their neglect today; many are found in his 2000 [sic] Short Hymns on Select Passages of the Holy Scriptures (1760), where even among such jewels the original of our no.862 shines with special brilliance. (The numerous OT ‘enemies’ are often transformed here into inbred or indwelling personal sins; sometimes the distinctive doctrines of freewill or perfectionism show up, and CW uses some bold language about circumcision: ‘cut off the foreskin of my heart’, etc.) Among many other collections, the later 1760s produced many hymns rooted in practical needs, from childbirth and school to family problems and retirement. In 1768 he moved from Bristol to Marylebone in London, mainly for the sake of his family; here he became the main preacher at the City Road Chapel; the classic Collection of Hymns for the Use of the People called Methodists was compiled by John for publication in 1780; at least 480 of its 525 hymns were by Charles—even though his elder brother thought that he spent too much time writing them. He also played the flute and organ, but the family’s musical talents were to bear greater fruit in his children and (notably) his grandson; see under S S Wesley in the Composers’ index.

J R Watson calls Charles ‘The William Shakespeare of hymnody’; many have dubbed him the poet of the heart—like ‘love’, a frequent climactic word in his verse. The concluding lines of his hymns are just one of many features which mark out his instinctive sureness of touch from the work of lesser contemporaries. While John’s heart (see below) was famously ‘strangely warmed’ in 1738, Charles’s was characteristically ‘set free’. He used an immense variety of metres, many of them original; some of his verse is anti-Calvinist polemic (the innocent-sounding word ‘all’ often flags up his Arminianism, and a general or universal atonement) and he was a master of comic and satirical rhymes. Like Bunyan in the previous century with ‘Giant Pope’ and ‘Giant Pagan’, Wesley consistently shows almost equal scorn for Romanism and Islam—‘superstition’s papal chain…that papal beast’, ‘Mahomet’s imposture…that Arab-thief’. His communion hymns, totalling 166 and leaning on the high-church theology of Daniel Brevint, are rarely found in the same hymnals as his more famous writing on gospel assurance. He loved and used his BCP (drawing richly on its Litany, for example, in Full of trembling expectation) and was clearly a reader of Matthew Henry’s Commentary on the whole Bible (1700) which he frequently versified. His masterly use and application of Scripture, if highly typological, is unparalleled in English hymnwriting. Perhaps his greatest work is the much-anthologised ‘Wrestling Jacob’ (Come, O thou traveller unknown) but the difficulty of finding a tune able to sustain the developing moods of its long narrative and reflection have kept this out of many hymnals including Praise! Far less known is the equally Christ-centred hymn on ‘Dreaming Jacob’, What doth the ladder mean? More often than not, Wesley is the best-represented author in UK hymn-books, as he is also in The New Oxford Book of Christian Verse (1981) with 11 entries from a total of 269 texts, 5 of which are hymns in general use. Of 980 hymns in the 1904 Methodist Hymn Book, 440 are by CW; its 1933 equivalent gives him 243 out of 984. In c1941, Edward Shillito quoted an anonymous Headmaster who said, ‘I hope you will let me advise all would-be hymn-writers to hold their pens until they have carefully studied Charles Wesley’. Like his brother, C Wesley has generated a large volume of other writing; among minor classics are The Evangelical Doctrines of Charles Wesley’s Hymns (J Ernest Rattenbury, 1941), The Hymns of Wesley and Watts (Bernard L Manning, 1942), recent biographies by Arnold Dallimore and Gary Best (respectively A Heart Set Free, 1988, and Charles Wesley: a biography, 2006), and The Handmaid of Piety by Edward Houghton (1992). It is Best’s book which serves as a corrective to much Wesleyan folklore, and most effectively brings Charles out from John’s shadow by giving credit where it is due. See also Carlton R Young’s 1995 anthology Music of the Heart: John and Charles Wesley on Music and Musicians. Meanwhile facsimile edns have been published of his hymns on the Nativity (1st edn 1745), the Lord’s Supper (with John W, also 1745), the Resurrection (1746), Ascension and Whitsuntide (1746) and the Trinity (1767). And while brother John’s career has been the basis of stage plays and musicals, inevitably involving Charles’s story, it is the younger and greater hymnwriter who uniquely prompted David Wright in 2006 to compose The Hymnical, a 2-part musical drama exploring CW’s life, hymns and contemporary relevance. Nos. 142*, 150, 160, 216, 227, 282, 324, 342, 344, 357, 359, 364, 438, 452, 458, 482, 495, 502, 511*, 523, 527, 529, 542, 555, 571, 583, 593, 595, 606, 625, 649, 682, 714, 718, 734, 742, 751, 776, 800, 808, 809, 812, 813, 822, 827, 828, 830, 837, 851, 862, 878*, 889, 940, 966.