Christian soldiers, onward go

- Exodus 14:15

- Exodus 15:1-2

- Exodus 15:20-21

- Exodus 40:36

- Joshua 5:13-15

- Judges 6:11-16

- 2 Chronicles 13:12

- Psalms 34:4

- Isaiah 25:8

- John 6:35

- John 6:48

- Acts 11:26

- Romans 13:12

- Romans 8:37

- 2 Corinthians 10:4

- 2 Corinthians 7:5

- Ephesians 6:10-13

- 1 Thessalonians 5:8

- 1 Timothy 6:12

- 2 Timothy 2:3

- 2 Timothy 4:7

- Hebrews 12:1-2

- Hebrews 2:10

- Revelation 21:4

- Revelation 7:17

- 886

Christian soldiers, onward go!

Jesus’ triumph you shall know;

fight the fight, maintain the strife,

strengthened with the bread of life.

2. Join the war and face the foe!

Christian soldiers, onward go;

boldly stand in danger’s hour,

trust your captain, prove his power.

3. Let your drooping hearts be glad,

march in heavenly armour clad;

fight, nor think the battle long-

soon shall victory tune your song.

4. Let not sorrow dim your eye,

soon shall every tear be dry;

let not fears your course impede-

great your strength if great your need.

5. Onward, then, in battle move!

More than conquerors you shall prove;

though opposed by many a foe,

Christian soldiers, onward go!

Verses 1-3, 5 © in this version Jubilate Hymns

This text has been altered by Praise!

An unaltered JUBILATE text can be found at www.jubilate.co.uk

Henry Kirke White 1785-1806

Frances S Colquhoun 1809-77 and others

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

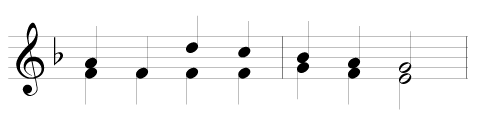

Tune

-

University College

Metre: - 77 77

Composer: - Gauntlett, Henry John

The story behind the hymn

Youthful talent, devotion and tragedy comprise some unavoidable factors in the story of this hymn. It is good that the extraordinary gifts of Henry Kirke White should be represented in our hymn-books. But in view of his other existing achievement, let alone what seems his unfulfilled potential, it is also sad that only a much-changed fragment should be his best-known memorial. Those who notice an author’s dates at the foot of a text may well look twice at these (as for example with 501, 769 etc), since he wrote the hymn at the age of 20 and died aged 21. His ten scribbled lines on the back of a Cambridge exam paper began Much in sorrow, oft in woe; we may be tempted to read that as prophetic, but for the fact that he already had a substantial body of verse to his credit, not all of it sorrowful. Even this draft might never have reached the status of a congregational hymn but for the editing of the 30-year old William B Collyer, whose 1812 book Hymns partly Collected and partly Original included 6 of his own lines added to White’s, and the further additions from Sara Fuller-Maitland in 1827. Her mother Bethia’s book Hymns for Private Devotion, Selected and Original (clearly still short of any intention of public use) featured an adaptation of White’s text by Sara, still in her teens and probably 14 when she wrote it. For whatever reason, editors have felt these youthful verses to be useful rather than sacrosanct; Edward Bickersteth introduced his revision in 1833, and William J Hall’s Mitre Hymn Book (1836) provided the first line Oft in danger, oft in woe. When adopted by A&M this became virtually the definitive text for nearly a century and a half. To bring the story up to date, HTC offered the 1st stz used here as the beginning of a revised text, and most of this Jubilate version is adopted. In view of this, the textual history is not easy to summarise. Under HKW’s original first line, however, Julian’s Dictionary covers the 19th-c instalment. Even in 1812 Collyer spoke of ‘the mutilated state of this hymn’, and published his expanded version as ‘The Christian soldier encouraged: 1 Timothy 6:12. H K White.’ Original lines include ‘Fight the fight, and worn with strife,/ steep with tears the bread of life … / Faint not—much doth yet remain,/ dreary is the long campaign’. Collyer’s additions have been largely abandoned, but Sara Fuller-Maitland’s contribution of 14 new lines (starting ‘Will ye flee in danger’s hour? …’) contains much of the now ‘traditional’ hymn. Sankey began with ‘Oft in sorrow …’ and had ‘Let not tears …’ at 4.3. New Jubilate lines are 1.2 and 2.4.

Henry J Gauntlett’s positive UNIVERSITY COLLEGE featured in his Church Hymn and Tune Book in 1852. It has become the usual tune for the words. Josiah Booth’s OAKFIELD was better known in N America.

A look at the authors

Colquhoun, Frances Sara (Fuller-Maitland)

b Shinfield Park, nr Reading, Berks 1809, d Edinburgh 1877. She wrote at least 3 hymns before the age of 18, including her adaptation of the hymn by H K White (qv) with which she became associated. Two of these were published in a collection compiled in 1827 by her mother, Mrs Bethia F-M of Stanstead Hall and Henley-on-Thames, Hymns for Private Devotion, Selected and Original. A third was added in its 1863 edn. Frances married John Colquhoun, son of Sir James C, in 1834. Her own collected verses Rhymes and Chimes appeared in 1876, but her name is now known chiefly (if at all) for her part in the editing of HKW’s hymn. No.886*.

White, Henry Kirke

b Cheapside, Nottingham 1785, d Cambridge 1806. His extraordinary talent was recognised early by his first teacher Mrs Garrington, who taught him between the ages of 3 and 5. He was given the best education his parents John and Mary could afford; his father was a butcher, and they had other children to consider as well. At 6 he began to learn maths at a school run by John Blanchard, a local clergyman. His delight was in reading, and by the age of 7 he would creep into the kitchen to teach the family servant to read and write. He began composing verse at 13; he gently satirised his teachers in some ‘School Lampoons’ which have not survived, and wrote some lines ‘On being confined to school one pleasant morning in Spring’, which have. His mother opened a ‘School for Young Ladies’ in order to provide more income for Henry, but at 14 he was obliged to start work in the hosiery trade. But he said that he could not bear the thought of spending 7 years of his life ‘in shining and folding up stockings’ (cf Gadsby, and composers Gardiner and Matthews!), and more verse emerged: ‘But O! I was not made for money-getting…’. A year later he joined a firm of solicitors, to whom he became articled at 17.

About this time he read Thomas Scott’s The Force of Truth, part autobiographical, part evangelistic; this led to his conversion in a hectic year in which he taught himself Lat, Gk, Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, and the rudiments of chemistry, electricity and astronomy. In 1803 his Clifton Grove, and Other Poems, was published; the title piece is a 490-line poem in rhyming couplets, followed by more than 600 blank-verse lines of a fine but unfinished piece Time. The first one breathes the spirit of Cowper (whose death he also commemorated in verse) and shows touches of Thos Gray or (even more recent) of Wordsworth, in its sensitivity to nature’s beauty, inward reflectiveness and also, like much of his other verse, a foreboding of death, often melancholy, even morbid: ‘…here waste the little remnant of my days’. The second poem is not the only one with some almost Miltonic lines; he also wrote to comic effect, but more common was the mood of ‘Consumption! silent cheater of the eye’, or ‘Fifty years hence, and who will hear of Henry?’. Many verses are a blend of stylised or classical archaism and intensely personal feeling weighed down with mournful adjectives, sickly tapers and dying screams.

HKW practised music and drawing, showing such outstanding and diverse talent that in 1804 he was released from his legal articles to enter St John’s Coll, Cambridge, soon winning an additional scholarship. Encouraged by such evangelical leaders as Charles Simeon and the youthful Henry Martyn, he prepared for ordination with more than usual discipline and devotion, not to mention his private self-examination, self-criticism, and anxiety about his increasing deafness. He set himself strict times for prayer after rising at 6.0, a daily 2-hour walk, and to drink tea only once a week. Many evenings were spent in sick-visiting. He became seriously weakened by overwork, and two visits to London for medical help did nothing to prevent the onset of tuberculosis complicated by other ailments; he died in his college rooms at the age of 21. His talent has been compared to that of other short-lived poets such as Keats, the very different Thos Chatterton, and Michael Bruce, qv. Byron, Josiah Conder, Wm B Collyer (qv) and some 8 other authors wrote verses in his memory; Coleridge admired his work, and in 1807 his greatest advocate Robert Southey, who had encouraged him from the first and later became an unhappy Poet Laureate, wrote a warmly affirming 40-page biography as a preface to White’s collected verse, to which several letters are added. Many of these are solemnly didactic (for a young man), some addressed to his mother and brothers, a few in Latin. He commends poetry, painting and music, but has no time for ballrooms, theatres, concerts or card-playing; and he believed that ‘It is a sign that a man’s heart is not right with God, when he finds fault with the Liturgy!’.

‘Chatterton is the only youthful poet whom he does not leave far behind him’—RS. Among his other verse is a paraphrase of most of Ps 22 and a strong ‘personal testimony’ text about the Bethlehem star (which is Christ), When marshalled on the nightly plain. Stevens’ Selection of Hymns included 2 more, but the one hymn for which he is known has been much reprinted and much altered, as here; see notes. No.886*.