From all that dwell beneath the skies

- Job 19:25

- Psalms 117

- Psalms 19:14

- Psalms 72:17-19

- Proverbs 23:11

- Isaiah 41:14

- Jeremiah 50:34

- Revelation 19:6

- Revelation 4:11

- Revelation 5:13

- 171

From all that dwell beneath the skies

let the Creator’s praise arise!

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Let the Redeemer’s name be sung

through every land, by every tongue!

Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

Hallelujah! Hallelujah! Hallelujah!

2. Eternal are your mercies, Lord;

eternal truth attends your word;

your praise shall sound from shore to shore

till suns shall rise and set no more.

Isaac Watts (1674-1748)

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

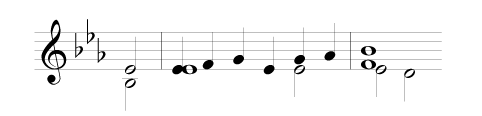

Tune

-

Lasst Uns Erfreuen

Metre: - LM with Hallelujahs

Composer: - Geistliche Kirchengesang

The story behind the hymn

This and the following item, older and newer respectively, are both rooted in the Psalms without being precise paraphrases; both are set to strong and much-used tunes, and both are found in Psalm collections—see notes to 117 and 149. Isaac Watts’ LM version of the 117th (he also rendered it in CM and SM) is filled out to hymn-length by the now customary addition of Hallelujahs. Whether working from the OT or the NT, the author loved to express combined praise to the Creator and the Redeemer. The only changes from his 1719 text in The Psalms of David Imitated … are ‘beneath’ for ‘below’ in line 1, and ‘your’ for ‘thy’ in stz 2.

The tune is Vaughan Williams’ arrangement of the German chorale tune LASST UNS ERFREUEN, named from the opening words of the Easter hymn to which they were set (Let us most heartily rejoice) and also known as EASTER HYMN/SONG, among other names. This was published in Cologne in 1623. It arrived in Britain with new words in EH, and the Easter connection was restored in the 1916 supplement to A&M. Many other texts have been set to this tune, including (from 1919 onwards) Draper’s All creatures of our God and King, 203, in what Dearmer called ‘multifarious and inappropriate use’. At least 16 other tunes have been used for these words in the 20th c alone; this one seems not inappropriate to a Psalm version, since (as Routley says) its opening phrase can be seen as a leitmotif of the Genevan reformation, as also in the tune known as [GENEVAN] PSALM 68 (105). See his further analysis in the Companion to Congregational Praise (1953) pp19–20; similarly, the 1999 Companion to Rejoice and Sing calls it ‘a remarkable example of economy, being built, by imitations and inversions, entirely on a four-note unit; the present form, by gathering the Alleluias together, is strengthened by rhetorical repetition’. See also Wesley Milgate, Songs of the People of God (1985 edn p 4) and John Wilson in HSB150, Jan 1981.

A look at the author

Watts, Isaac

b Southampton 1674, d Stoke Newington, Middx 1748. King Edward VI Grammar Sch, Southampton, and private tuition; he showed outstanding early promise as a linguist and writer of verse. He belonged to the Above Bar Independent Chapel, Southampton, where his father was a leading member and consequently endured persecution and prison for illegal ‘Dissent’. Some of the historic local landmarks in the family history, however, have question-marks over their precise location. But for Isaac junior’s undoubted first hymnwriting, see no.486 and note; the Psalm paraphrases then in use often were, or resembled, the Sternhold and Hopkins ‘Old Version’, described by Thos Campbell as written ‘with the best intentions and the worst taste’, or possibly the similarly laboured versions of Thomas Barton. His solitary marriage proposal to the gifted Elizabeth Singer was not the only one she rejected, but they remained friends, and her own hymns (as ‘Mrs Rowe’) were highly praised and remained in print until at least around 1900. After further study at home, in the year after Horae Lyricae (published 1705) and at the age of 32, Watts became Pastor of the renowned Mark Lane Chapel in the City of London and private tutor/chaplain to the Abney family at Theobalds (Herts) and Stoke Newington. Chronic ill health prevented him from enjoying a more extensive or prolonged London ministry, though with the care of a loving household he lived to be 74.

In 1707 came the 3 books of Hymns and Spiritual Songs, and in 1719, The Psalms of David Imitated in the Language of the New Testament, and Applied to the Christian State and Worship. As he is acknowledged as the father of the English hymn, so he became the pioneer of metrical Psalms with a Christian perspective. He is acknowledged as such by Robin Leaver who once added, a touch prematurely, that he was equally the assassin of the English metrical Psalm! His own ‘design’ was ‘to accommodate the Book of Psalms to Christian Worship…It is necessary to divest David and Asaph, etc, of every other character but that of a Psalmist and a Saint, and to make them always speak the common sense of a Christian’. His ‘Author’s Preface’ from which this is taken is a brief apologia for his aim and method; he desires to serve all ‘sincere Christians’ rather than any one church party, and he explains the careful omissions and interpretations of hard places. Above all, he is ‘fully satisfied, that more honour is done to our blessed Saviour, by speaking his name, his graces and actions, in our own language…than by going back again to the Jewish forms of worship, and the language of types and figures.’

Not always accepted by his contemporaries, he nevertheless laid the foundations on which Charles Wesley and others built. Some of his hymns and Psalm versions are among the finest in the language and still in worldwide use; Congregational Praise (1951) has 48 of his hymns, and CH (2004 edn), 59. Many of these are found in the early sections of a thematically-arranged hymn-book, under ‘God the Father and Creator’ or similar category.

With his best-selling Divine Songs attempted in Easy Language, for the sake of Children (1715) he was the most popular children’s author in his day (and well into the 19th c); those who understandably recoil today at some of them would do well to see what else was on offer, even 100 or more years later. Watts, too, was a respected poet, preacher and author of many doctrinal prose works. He corresponded as regularly as conditions then allowed with the leaders of the remarkable work in New England. A tantalisingly brief reference in John Wesley’s Journal for 4 Oct 1738 (neither repeated nor paralleled, and less than 5 months after JW’s ‘Aldersgate experience’), reads: ‘1.30 at Dr Watts’. conversed; 2.30 walked, singing, conversed…’. Dr Samuel Johnson and J Wesley used his work extensively, the former including many quotations from Watts in his 1755 Dictionary of the English Language. His work on Logic became a textbook in the universities from which he was barred because of his nonconformity. The current Oxford Book of English Verse (1999) includes 5 items by IW including his 2 best-known hymns. Further details are found in biographies by Arthur P Davis (1943), David Fountain (1974) and others, the 1974 Annual Lecture of the Evangelical Library by S M Houghton, and publications of the British and N American Hymn Societies (by Norman Hope, 1947) and the Congregational Library Annual Lecture (by Alan Argent, 1999). See also Montgomery’s 4 pages in his 1825 ‘Introductory Essay’ in The Christian Psalmist, where he calls Watts ‘the greatest name among hymnwriters…[ who] may almost be called the inventor of hymns in our language’; and the final chapter of Gordon Rupp’s Six Makers of English Religion (1957). The 1951 Congregational Praise is rare among hymn-books for including more texts by Watts than by C Wesley. Nos.5*, 122, 124, 136, 146, 163, 164, 171, 189, 208, 214, 231, 232, 241, 255, 260, 264, 265, 300, 312, 363, 401, 411, 453, 486, 491, 505, 520, 549, 557, 560, 580, 633, 653, 692, 709*, 780, 783, 792, 794, 807, 969, 974*, 975.