Go, labour on; spend and be spent

- Psalms 40:8

- Matthew 10:24-25

- Matthew 19:21

- Matthew 20:1-16

- Matthew 22:9-10

- Matthew 25:6

- Matthew 26:41

- Matthew 6:19-21

- Mark 10:21

- Mark 14:38

- Luke 12:33-34

- Luke 14:23

- Luke 18:1

- Luke 18:22

- Luke 21:36

- Luke 6:40

- John 13:15-16

- John 3:29

- John 4:34

- John 6:38

- John 9:4

- 1 Corinthians 15:58

- 2 Corinthians 12:15

- Galatians 6:9

- Ephesians 5:16

- Philippians 3:7-8

- Colossians 2:15

- 1 Thessalonians 2:9

- 1 Timothy 6:17-19

- Hebrews 12:3-11

- James 5:19-20

- Revelation 22:12

- Revelation 22:20

- 855

Go, labour on; spend and be spent,

your joy to do the Father’s will;

it is the way the Master went:

should not the servant tread it still?

2. Go, labour on, true wealth to know;

find heavenly gain in earthly loss:

what if unloved, unpraised you go?

Your Master triumphed through his cross.

3. Go, labour on while it is day;

the world’s dark night is hastening on:

work with all speed, while still you may;

see that the gospel’s work is done.

4. Toil on, faint not, keep watch and pray;

be wise the straying soul to win:

go out into the world’s highway,

compel the wanderer to come in.

5. Toil on and in your toil rejoice;

for toil comes rest, for exile home:

soon you shall hear the Bridegroom’s voice,

the midnight cry, ‘Behold, I come!’

© In this version Praise Trust

Horatius Bonar 1808-89

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

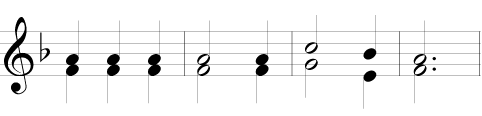

Tune

-

Arizona

Metre: - LM (Long Metre: 88 88)

Composer: - Earnshaw, Robert Henry

The story behind the hymn

Opening section 8j on ‘Zeal in service’ is the first hymn written by Horatius Bonar for adults rather than children or young people. K Parry, J Telford and G Whitehead say that he wrote it in 1836 for his fellow workers at Leith, on the N edge of Edinburgh overlooking the Firth of Forth, where he began his ministry. Some books give the date as 1843—the year not only of a return visit on a mission in Leith, but also of the ‘Disruption’ when Bonar left the Church of Scotland for the new Free Church. It was certainly printed at Kelso in a leaflet of mission hymns, then in the author’s Songs for the Wilderness (1843), headed ‘Labour for Christ’. Subsequently it entered many other hymnals including editions of the Church Hymnary used by both the CofS and the United Free Church. Its original 8 stzs are now commonly reduced, even in Scotland, to 5 or 6. Of these, the 2nd of the usual selection presents several problems; originally ‘…’tis not for naught;/ thy earthly loss is heavenly gain:/ men heed thee, love thee, praise thee not;/ the Master praises—what are men?’ 3.3–4 read ‘Speed, speed thy work, cast sloth away;/ it is not thus that souls are won’ and 4.2 had ‘erring’. Among omitted lines are ‘… your hands are weak,/ your knees are faint, your soul cast down …’ and ‘Men die in darkness at your side/ without a hope to cheer the tomb …’ Several biblical references undergird the hymn; among the clearest are Matthew 10:25 and 25:6, and John 9:4.

The author wrote his words for THE OLD HUNDREDTH (100A), possibly as a ‘safe’ stand-by tune. It is vital not to depress the congregation by dragging the playing and singing of the hymn; so the Revised Church Hymnary chose the bold DEUS TUORUM MILITUM and the Anglican Hymn Book (for its 7 stzs), R S Thatcher’s WILDERNESS, from 1936. But these in turn do not always match the solemnity of some lines. WHITBURN (637) has been in wide use; Robert Earnshaw’s ARIZONA was first printed on a leaflet with a hymn for travellers by Henry Burton. Since then it has been set to several varied texts; ‘Its popularity’, said Erik Routley generously, ‘places it beyond the reach of useful criticism.’

A look at the author

Bonar, Horatius

b Edinburgh 1808, d Edinburgh 1889. Edinburgh High Sch and Univ; licensed to preach (Ch of Scotland) and became asst. to the Minister at Leith, where his first hymns were written as a response to the children who needed more than archaic Psalmody. With other young men he engaged in mission work in the city’s homes, courtyards and alleyways. Five of his own 9 children died while young. From 1837 he was Minister of the North Parish beside the Tweed in Kelso; then at the 1843 ‘disruption’ he became a founder member of the Free Ch of Scotland but (unlike many) was able to continue his existing ministry at Kelso. He edited the Quarterly Journal of Prophecy 1848–73; Hon DD (Aberdeen) 1853; he visited Palestine 1855–6 and drew much imagery from his experiences there. From 1866, he was Minister of the Chalmers Memorial Free Ch, Edinburgh; from 1883, Moderator of the Free Church’s General Assembly. ‘Always a Presbyterian’, and a keen student of the Classics and early church fathers, he wrote about one book every year; his Words to Winners of Souls has proved of special value to Jerry E White, President of The Navigators a century later. Bonar was a frequent attender and speaker at London’s Mildmay Conferences; see under W Pennefather. As well as being committed to prayer, preaching and visiting, he wrote some 600 warmly evangelical hymns and other Psalm paraphrases, earning him the title ‘prince of Scottish hymn-writers’. Some were designed specifically for the visiting American singer (with Moody), Ira D Sankey. About 100 reached publication; many were written very rapidly but enjoyed great popularity in their day, and his lifetime witnessed a great change in what was sung in Scottish churches. The Keswick Hymn Book (1938) featured 17 of these and Hymns of Faith (1964), 13. But while the 1898 edn of the Scottish Church Hymnary included 18 texts (more than from any other author), CH3 (1975) found room for 8 and the 2005 book reduces these to 5; posterity has been less than kind to his wider reputation. Among those not quite forgotten is ‘All that I was – my sins, my guilt,/ my death was all my own;/ all that I am I owe to thee,/ my gracious God alone.’

A clause in Bonar’s will stipulated that no memoir should be published, but in the year after his death his son H N Bonar published Until the Day Break, and other Hymns and poems left behind, and in 1904 and further hymn selection with notes. Julian laments the hymnwriter’s ‘absolute indifference to dates and details’, while Routley is lukewarm about much of his work, and on receiving the news of his death, Ellerton acknowledged his limited vision, unpoetic lines and occasional triteness—‘But he is a believer. He speaks of that which he knows; of him whom he loves, and whom, God be praised, he now sees at last’—JE, 1889. Like this English hymnologist, several other historians have at least admitted Scotland’s debt to one who probably did more than anyone to bring hymns into the mainstream of the church’s and the nation’s song. Nos.151, 271, 581, 648, 701, 710, 793, 801, 838, 855, 874, 1284