Heal us, Immanuel, hear our prayer

- Genesis 18:25

- Isaiah 7:14

- Matthew 1:23

- Matthew 12:15

- Matthew 14:14

- Matthew 14:35-36

- Matthew 8:16

- Matthew 9:20-22

- Mark 1:32-34

- Mark 3:10

- Mark 5:25-34

- Mark 6:55-56

- Mark 9:14-29

- Luke 4:40

- Luke 6:17-19

- Luke 8:43-48

- 680

Heal us, Immanuel, hear our prayer;

we wait to feel your touch.

Deep-wounded souls to you draw near

and, Saviour, we are such.

2. Our faith is feeble, we confess;

we faintly trust your word.

And will you pity us the less?

Be that far from you, Lord!

3. Remember him who once applied

with trembling for relief:

‘Lord, I believe,’ aloud he cried,

‘O help my unbelief!’

4. She who reached out in her distress,

as at your feet she fell,

was answered, ‘Daughter, go in peace;

your faith has made you well!’

5. Concealed amid the growing throng,

she trembled in her fright;

and though her faith was clear and strong

she would have shunned your sight.

6. Like her, with hopes and fears, we come

to touch you if we may;

O send us not despairing home;

send none unhealed away!

© In this version Praise Trust

William Cowper 1731-1800

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

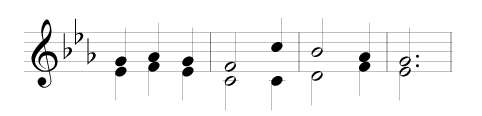

Tune

-

Strood

Metre: - CM (Common Metre: 86 86)

Composer: - Badrick, Albert E

The story behind the hymn

Not the least value of this text by William Cowper from the 1779 Olney Hymns lies in its prayerful treatment of two Gospel incidents of healing, from Mark 9:24 and 5:34 (and parallels) respectively. These are the key vv in the original footnotes, but the hymn is placed under Exodus in the Bible arrangement, with the heading ‘JEHOVAH-ROPHI: I am the LORD that healeth thee. Chap.xv.’ It is one of 6 from that book, Cowper’s other contribution being ‘JEHOVAH-NISSI: The LORD my banner. Chap.vvii.15. By whom was David taught to aim the dreadful blow. The original began ‘Heal us, Emmanuel, here we are, waiting … / … souls to thee repair’, which most books (but not PHRW) now change. 3.3 had ‘with tears’, and stz 4 (naturally based on the AV) read ‘She too, who touch’d thee in the press,/ and healing virtue stole/ … hath made thee whole.’ The 5th stz (often now omitted as in CH, GH, PHRW etc) read ‘… the gath’ring throng,/ she would have shunned thy view,/ and if her faith was firm and strong,/ had strong misgivings too.’ A coolly critical note in the Companion to Rejoice and Sing does however observe with some truth that ‘What the two [Gospel] stories had in common, for Cowper, was the almost unbearable tension between belief and unbelief, which dominated his own spiritual life and from which he was never wholly free.’ Julian is more appreciative of the hymn and its sources.

STROOD, named from the town near Rochester in Kent, was composed by Albert E Badrick in the early 20th c. He would travel down from the north in the 1930s to conduct the Strood Gospel Mission’s Silver Band, in whose honour he wrote this tune. The band competed with others at the old Crystal Palace, and subsequently at Alexandra Palace, until after the 1939–45 war it gave way to more directly evangelical activities; some of its musicians then transferred to different bands. Other tunes in use include ALBANO and STRACATHRO (607, 343).

A look at the author

Cowper, William

(pronounced ‘Cooper’), b Great Berkhamsted, Herts 1731, d East Dereham, Norfolk 1800. Permanently affected by the loss of his mother in childhood, at 6 he was sent to boarding sch at nearby Markyate, then to Westminster Sch. Although he was bullied, he enjoyed most kinds of sport and his gift for comic verse appeared early—always gentle rather than savage. Articled to an attorney, he was called to the bar in 1754 but never practised in the legal profession. He was recommended for the post of Clerk to the Journals of the House of Lords, but suffered panic attacks at the thought of being publicly examined, acute shyness merging into despair and leading to his first attempt at suicide. A possible marriage to cousin Theodora was vetoed by her family; she remained single but fond of him, and almost certainly helped him with anonymous financial gifts for many years. Support in other ways came from his brother John, later to be ordained, and the hymnwriter and editor Martin Madan. He found respite in an asylum (‘Collegium Insanorum’) at St Albans run by the evangelical Dr Nathanael Cotton ( 1707–88, the same dates as C Wesley, some of whose own hymns might easily speak for Cowper). During his time there (in 1764) he readily testified to gaining a clear view of God’s grace from Rom 3:25; he then moved to Huntingdon to settle with Morley and Mary Unwin and their teenage children at the vicarage. But in 1767 Morley, the vicar, died from the severe injuries sustained when he was thrown from his horse. The household found a congenial evangelical friend in John Newton (qv) and moved to Olney to become his neighbours and parishioners, coming to value his preaching, his warm friendship and eventually an unlikely writing partnership.

William became affectionately known in the village as ‘Sir Cowper’, a lover of the still rural scenery and of ‘all creatures, great and small’ including the tame hares which had the run of his house. In 1773 he had a further breakdown; Newton planned what became the Olney Hymns as a means of praising God, teaching his growing midweek congregation, and also of lifting his friend from depression by a practical project well within his great abilities and close to his heart. Cowper’s contributions, many of which have featured in major hymn-collections ever since, come mainly in the early sections and are marked ‘C’. These were published in 1779; soon after which (1782, 1785) his two main volumes of poems including satires appeared, which confirmed his position in the literary world. After Newton was appointed to his London living in 1780, Cowper, Mrs Unwin and remaining household moved a mile of so to Weston Underwood, At one point William and Mary seemed set for marriage but again the poet’s nerves failed him, and while she had cared for him, in her own final illness the roles were reversed. His poem ‘To Mary’ is a poignant memorial of that warm but interrupted friendship. But Cowper would soon need further support, which after her death in 1796 he found notably in (the Rev) John Johnson; Cowper’s last 4 years were spent at East Dereham, Norfolk, in whose parish ch are some notable memorials. Sadly, gloom descended on his mind for some time before the end.

But his legacy, sacred and secular, remains; he is one of a small handful of major poets to feature in hymn-books, and of an even smaller group of those who set out to write hymns. Among the less-known are some translations, not published till 1801, from the French of the ‘quietist’ Madame Guyon (1648–1717). Although many of his hymns are deeply personal, several remain as standard hymns in mainstream books: The 1965 Anglican Hymn Book has 9 and Common Worship (2000) 5, while CH 2004 includes 10. He declined the post of Poet Laureate, but his long poem in 6 books The Task (1785), beginning ‘I sing the sofa…’, enjoyed great success; its lines on the evangelical preacher (‘I say the pulpit…Must stand acknowledged, while the world shall stand’) are almost unique in serious literature, in celebrating such a ministry without caricature, ridicule or contempt. He translated from Lat and Gk (but not hymns); among his lighter verse John Gilpin (1782) has remained a favourite and even Bernard Shaw loved it. Cowper also wrote eloquently against the slave trade, in support of Wilberforce, and (from experience) against public schools. His spiritual struggles have been compared with those of the youthful Bunyan (whose The Pilgrim’s Progress sometimes finds an echo in Cowper’s hymns), and his ‘pre-romantic’ verse to that of James Thompson and Wordsworth. He finds a place in virtually all representative collections of English verse; the 1972 ‘New Oxford’ book typically features 6 items including his most quoted hymn (256) and the despairing but still finely-written ‘The castaway’, ‘Obscurest night involved the sky’. These are 2 of the more meagre 3 items in its 1999 successor. Among the many studies of the man and his work, the more reliable ones are by those who share or at least understand his faith, including major work by George M Ella (William Cowper: Poet of Paradise, 1993) and more briefly by Elsie Houghton (1982), Faith Cook (2005), and the Day One ‘Travel Guide’ by Paul Williams (2007). The popular durability of Cowper’s verse has again been demonstrated in the 21st century in public recitals by the ‘poetry performer’ Lance Pierson; see also under G Herbert. The former Olney vicarage now houses the Newton and Cowper Museum. Nos.256, 444, 562, 609, 615, 680, 811, 876.