How sweet the name of Jesus sounds

- Exodus 16:14-15

- Exodus 16:35

- Numbers 11:6-9

- Deuteronomy 18:15-18

- Psalms 104:33

- Psalms 119:114

- Psalms 143:9

- Psalms 146:2

- Psalms 18:2

- Psalms 32:7

- Psalms 66:18-19

- Psalms 69:36

- Isaiah 32:2

- Micah 5:4

- Zechariah 6:13

- Matthew 1:21

- Matthew 1:25

- Matthew 11:28-29

- Matthew 13:57

- Matthew 21:11

- Mark 6:4

- Luke 1:31

- Luke 13:33

- Luke 18:13-14

- Luke 2:21

- Luke 24:19-23

- Luke 4:24

- John 1:12

- John 1:16

- John 10:11

- John 10:14-15

- John 14:6

- John 17:24

- John 18:37

- John 20:28

- John 20:31

- John 4:19

- John 4:44

- Acts 3:22

- Acts 7:37

- 1 Corinthians 10:4

- 1 Corinthians 3:11

- Ephesians 2:18

- Ephesians 3:8

- Philippians 1:21-23

- Colossians 3:4

- Hebrews 2:17-18

- 1 Peter 2:7

- 1 John 3:1-2

- Revelation 12:10

- 299

How sweet the name of Jesus sounds

in a believer’s ear!

It soothes our sorrows, heals our wounds

and drives away our fear.

2. It makes the wounded spirit whole,

and calms each heart oppressed;

it’s manna to the hungry soul,

and to the weary rest.

3. Dear name, the rock on which I build,

my shield and hiding-place;

my never-failing treasury, filled

with boundless stores of grace!

4. By you my prayers acceptance gain,

although with sin defiled;

Satan accuses me in vain

since I am God’s own child.

5. Jesus, my shepherd, brother, friend,

my Prophet, Priest and King,

my Lord, my life, my way, my end,

accept the praise I bring.

6. Weak is the effort of my heart,

and cold my warmest thought;

but when I see you as you are,

I’ll praise you as I ought.

7. Till then I would your love proclaim

with every fleeting breath;

and may the music of your name

refresh my soul in death.

John Newton (1725-1807)

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

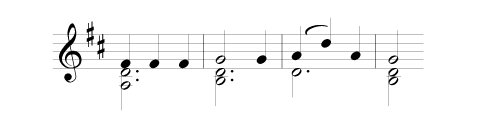

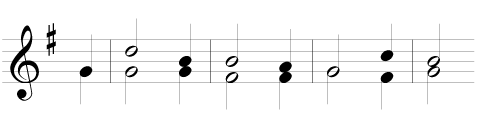

Tunes

-

Rachel (extended)

Metre: - CMD (Common Metre Double: 86 86 D)

Composer: - Bowater, Chris

-

Godre'r Coed

Metre: - CM (Common Metre: 86 86)

Composer: - Davies, Matthew William

The story behind the hymn

In the arrangement of the 1779 Olney Hymns, Book 1 is ‘On select Texts of Scripture’, in Bible order. So as Amazing grace (here 772) is the only entry under 1 Chronicles, so this hymn is the sole representative for ‘Solomon’s Song’: ‘Hymn LVII. The name of JESUS. Chap.i:3.’ The key words in the text are ‘thy name is as ointment poured forth …’ These two hymns, currently the best known of John Newton’s (he has 16 in Praise!), remarkably share most of their respective first lines: ‘… how sweet the sound’ and ‘How sweet the name … sounds’. The sound of the word, and the name, were all the sweeter to ‘the old African blasphemer’, as he used to call himself; his own language, once foul enough to alarm even his fellow-sailors, was not only cleansed but entirely renewed in the service of his Lord Jesus. There is much more here, of course, than the traditional (allegorical) reading of the Song of Songs, and both OT and NT imagery and titles would provide a useful Bible study, as indeed do his own sermon notes on Song of Songs 1:3, preserved at Olney. The hymn has the theme of 312 explored with the tenderness of 741. In a typical passage from a sermon, Newton says that Christ permits his people ‘to claim the most tender relation to him, and to call him their Brother, their Friend, and their Husband’.

Most hymnals emend Newton slightly, and CH and GH are among many omitting stz 4; here the changes are comparatively minor. Stz 1 is now gender-inclusive (no longer ‘his’ sorrows, etc) and 2.2 replaces ‘… troubled breast’. More sensitive for different reasons are 5.1 and 6.3, and there are arguments on both sides. In stz 5, ‘husband’ changes to ‘brother’ (as in CH, but not GH) since the ‘bridegroom’ belongs to the church rather than to the individual believer; this change can be traced back at least to 1852. Many other versions of the line are in print, including ‘Jesus, my shepherd and my friend’ in Rejoice and Sing (1991). As with other phrases, Charles Wesley got in first with his 1749 hymn O thou our husband, brother, friend; but could Newton the ex-seaman have meant after all ‘ship’s husband’—the ‘husbandman’ who attends to all the stores and provisions for the crew? See J R Watson, An Annotated Anthology of Hymns, 2002, p111; but JN’s sermon shows no hint of this usage. In stz 6 the exact rhyme in line 3 becomes an assonance rather than retaining the archaic ‘art’ or recasting entirely. This is also the preferred option in HTC and Together in Song: Australian Hymn Book II (1999). Some pairs of stzs have a connecting link: wounds/wounded, praise(noun)/praise(verb), etc.

It was the 1861 A&M which first set the words to ST PETER; two other possible tunes are suggested here (126 and 737) while the printed choice is Chris Bowater’s RACHEL. He composed it when his first child, Rachel, was seriously ill, and ‘the hymn became a great source of comfort and inspiration’. Rachel survived to become a GP and a mother. The melody clearly owes something to Drink to me only with thine eyes, c1770, which has also been set to Newton’s words and others (sometimes re-named PROSPECT), perhaps in the spirit of his own adapted scriptural source. This appeared as the 2nd choice in HTC 1982 (arranged, as here, by Noël Tredinnick) and has been widely used since then. Being an 8-line CMD tune, it requires the repetition of its second half for stz 7, which can be seen (and heard) as a positive advantage.

A look at the author

Newton, John

b Wapping, E London 1725, d City of London 1807. His early life ‘might form the groundwork of a story by Defoe, but that it transcends all fiction’—Ellerton. When he was not quite 7 his godly mother died; his father, a merchant navy captain, found the new situation, and his son, hard to handle but took him to sea when he was 11. Back on shore at 18 or 19 John was press-ganged for the royal navy, and recaptured and flogged after desertion. A life of increasing godlessness and depravity on board ship was relieved only by his love for Mary Catlett of Chatham, Kent, whom he had met when he was 17 and she was 14. But he had to sink as low as to be ‘a servant of slaves’ (JN) on the W African coast, and have many brushes with death, when the only book he had was a copy of Euclid’s geometry. Strangely still a non-swimmer, he was almost drowned during a storm at sea before (even more surprisingly) he dipped into The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis and eventually ‘came to himself’. After a series of providential events he finally arrived on the Irish coast. Now 23, he renewed his attachment to Mary before another African voyage as ship’s mate; this time he was laid low by fever, but during that time made his decisive Christian commitment—or rather, simply cast himself on the mercy of God in Christ. In 1750 John and Mary were married. He accompanied or captained several ships on the notorious Atlantic slavetrade, and came with what seems surprising slowness to see the inconsistency of this with his growing Christian faith. Eventually he was to be a supporter of Wm Wilberforce, Thos Clarkson, Granville Sharp and James Stephen; while he came to oppose slavery itself, he was not as consistent or prominent a campaigner as they, and did not list the trade among Britain’s national sins. Further illness in 1754 compelled him to give up his seafaring career and he spent 9 years as Liverpool’s tide surveyor, including leading a large team of inspectors for contraband. He made a friend of Wm Grimshaw, vicar of Haworth, and of Lord Dartmouth who read his story in ms (see also under Fawcett and Haweis). With Dartmouth’s help and after many difficulties he was admitted to ordination (CofE) and in 1764 became curate, effectively incumbent, of Olney, Bucks.

Here Newton became the means of enlightening his neighbour clergyman Thos Scott, whose cynical rationalism was transformed through Newton’s patient and courteous witness into clear evangelical faith. Scott became a noted Bible commentator and published his testimony (re-issued in the 20th c) as The Force of Truth. More famously, Newton became the close friend of William Cowper (qv); he compiled the Olney Hymns (1779) partly with a view to helping Cowper to regain a sense of purpose and use his poetic gifts for the gospel; JN’s Preface claims that ‘I am not conscious of having written a single line with an intention, either to flatter or to offend any party or person on earth’. While many of Newton’s hymns on prayer are searching and lasting (and ‘grace’ is a favourite word), his positive, objective cheerfulness generally provides an excellent foil to Cowper’s sometimes wistful and questioning introspection. Comparisons of the two men’s contributions are common; Montgomery is typical in elevating Cowper, but Lord Selborne speaks for others in balancing Newton’s ‘manliness’ with his friend’s ‘tenderness’, and in clear biblical doctrine they were one. One unexpected result of the book and a sign of its wide and enduring influence was the spur it gave to the RC convert F W Faber (1814–63), as he acknowledged, to try to emulate it for his fellow-Romans some 75 years later. Some extraordinary ‘invective’ (Dr W T Cairns’s word, HSB16, July 1941) has been directed against Newton, by David Cecil and others, for his supposedly malign influence on Cowper. His article examines the evidence for and against such assertions, observing incidentally that ‘neither Cowper nor Newton seems to have been conscious of the alleged unfortunate effect of this association’. JN features more positively in some lines from Wordsworth’s major autobiographical poem The Prelude (begun 1798, final posthumous version 1850), Bk 6.

In 1779 Newton became Rector of St Mary Woolnoth in the City of London, where at that time evangelical incumbents were almost unknown. He ministered there until his death, having lost much of his hearing and sight, surviving his beloved Mary by 17 years. Among other publications, some posthumous, were his sermons and even more remarkable letters to many friends (Cardiphonia, partly republished in the 1960s). A memorial tablet in the city church outlines his story, which has often been made the subject of popular biographies. Among recent books are Brian Edwards’ Through Many Dangers (1975, revised edn 1980), Bernard Braley’s study in Hymnwriters 2 (1989), and Steve Turner’s Amazing Grace (2002; see Introduction to the present book); all of which are complemented by Adam Hochschild’s eloquently disturbing Bury the Chains: the British struggle to abolish slavery (2005). Until fairly recently brief biographical notes on Newton made no mention of Amazing grace; for many now it seems to be the most important fact about him. The John Newton Project currently aims to promote evangelical renewal through the study and appreciation of Newton’s contribution to gospel work and the ending of the slave trade 2 centuries ago. In 2000 Marilynn Rouse, founder leader of the Project, published her edited and annotated edn of Richard Cecil’s 1808 biography. Nos.276, 299, 313*, 326, 570, 600, 602, 603, 607, 717, 767, 772, 791, 875, 903, 958.