I know that my Redeemer lives

- Deuteronomy 18:15-18

- Job 19:25

- Isaiah 41:14

- Matthew 13:57

- Matthew 28:8

- Mark 6:4

- Luke 13:33

- Luke 24:19-23

- Luke 24:41

- Luke 24:50-51

- Luke 4:24

- John 13:1

- John 14:19

- John 14:2-3

- John 18:37

- John 20:20

- John 20:31

- John 21:24

- John 4:44

- Acts 13:34

- Acts 17:25

- Acts 17:31

- Acts 3:22

- Acts 7:37

- Romans 6:9

- Romans 8:34

- Ephesians 1:22

- Colossians 1:17-18

- Hebrews 10:22

- Hebrews 13:8

- Hebrews 2:17-18

- Hebrews 7:25

- 1 John 5:13

- Revelation 1:18

- 462

I know that my redeemer lives:

what joy this great assurance gives!

He lives, he lives, who once was dead,

he lives, my ever-living head.

2. He lives, triumphant from the grave;

he lives, eternally to save;

he lives to bless me with his love,

he lives to plead for me above.

3. He lives, my kind, wise, constant friend,

he lives and loves me to the end;

he lives, and while he lives I’ll sing,

‘Jesus, my Prophet, Priest and King.’

4. He lives and grants me daily breath;

he lives and I shall conquer death:

he lives my dwelling to prepare;

he lives to bring me safely there.

5. He lives, all glory to his name!

He lives, unchangeably the same!

What joy this great assurance gives:

I know that my Redeemer lives!

Samuel Medley 1738-99

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

Tunes

-

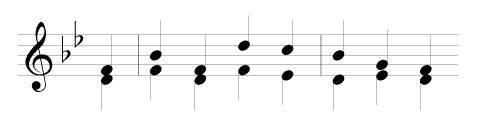

Church Triumphant

Metre: - LM (Long Metre: 88 88)

Composer: - Elliott, James William

-

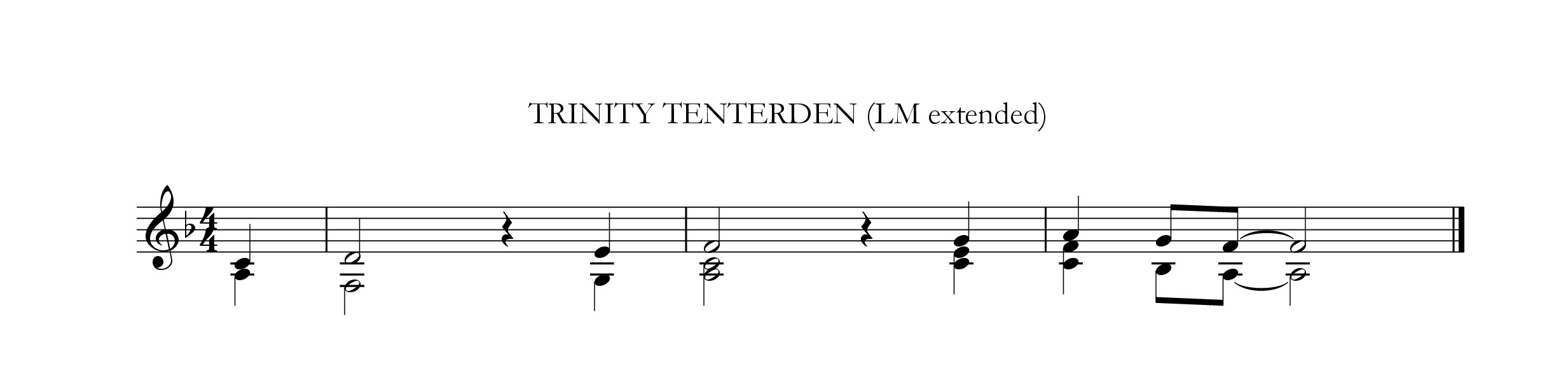

Trinity Tenterden

Metre: - LM extended

Composer: - Mawson, Linda

The story behind the hymn

Built on its opening from Job 19:25, (and a bold, almost direct quote from Anne Steele’s He lives, the great Redeemer lives! What joy the blest assurance gives) this hymn is structured throughout on the repeated ‘He lives’. These words, which in any of its varied revisions begins all but two or three of its lines, make the text something of a tour de force. Handel’s Messiah features one of his most celebrated solos, ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth’; other hymns before or since have used the same beginning (see 907), so more than 6 words are needed when indexing. Samuel Medley’s original 9 stzs appeared anonymously in George Whitefield’s Psalms and Hymns, 21st edn (!) 1775, and again in a 1793 collection from Richard De Courcy. It was then included in the author’s posthumous Hymns in 1800, since when many variations and selections of stzs and lines have been printed. Most of the lines here are virtually as first written, though not all in their original places. Minor variations in the present book include ‘great’ for ‘blessed’ and ‘ever-living’ for ‘everlasting’ in stz 1; ‘he lives and loves me’ for ‘he still will keep me’ in stz 3. To see this editing in perspective it is necessary only to compare the texts in CH/PHRW (similar except for stz 1), GH, and Christian Worship (1976). The author was acknowledged to be something of an eccentric, but his friends were glad to record that his dying words, after much comforting and prayerful conversation with them and some of his family, were said to be ‘Glory, glory! Home, home!’; cf stzs 4 and 5. For notes on the regularly-used tune CHURCH TRIUMPHANT see 47. The 1965 Anglican Hymn Book is among those using LASST UNS ERFREUEN (EASTER SONG, 171); the added ‘Hallelujahs’ may be one reason why the hymn is reduced there to 4 stzs.

A look at the author

Medley, Samuel

b Cheshunt, Herts 1738, d Liverpool 1799. Educated at the school run at Enfield by his maternal grandfather Wm Tonge, where he showed early promise and a keen memory. But at 14 he was apprenticed to a London oil merchant. When war broke out in 1756 apprentices were allowed to complete their services in the army or navy, and Samuel willingly (though not without family opposition) became a 17-yr old midshipman. Favoured by the captain, a family friend, he prospered outwardly and gained promotion without any signs of spiritual life; like his older contemporary Jn Newton he only used his lively wit for frivolity and worse. Moments of serious thought came to a head in a desperate sea-battle between the English and French off the Portuguese coast. Threatened with amputation of a wounded leg, he turned to the Psalms in his neglected Bible, prayed that night for healing, and was answered. Back on shore, he needed recuperation but also drifted back into carelessness, longing again for the sea. But one Sunday evening his grandfather read to him a sermon by Isaac Watts on Isa 42:6–7. This time the young man truly repented and believed; his debt to Watts may be reflected later in such (almost) borrowed lines as ‘love how amazing, how divine…’ (from his On Christ alone, another suggestive opening). He also used lines from Anne Steele: ‘What joy the blest assurance gives!’, and others. After his conversion he spent his time in studying the Bible in Heb and Gk, with other classic books; soon he was able to hear the preaching of Andrew Gifford, his pastor, and George Whitefield. Leaving the navy, he opened a school, and after marriage to Mary Gill moved with the school to Soho. From 1764 he began to study under Gifford with a view to public gospel ministry, which he formally entered into in Aug 1766. 2 years later he became pastor of a Particular Baptist Ch in Watford, then the town’s only dissenting congregation. After strenuous labours there, and now with a family, he moved to Liverpool in 1772 to take up a struggling cause which he served for the next 27 yrs until his death. He also regularly visited London to preach at Tottenham Court Rd and Rowland Hill’s Surrey Chapel. The Liverpool congregation grew, and in 1789 its enlarged chapel became one of the country’s biggest.

His sermons were vivid, sometimes on a single word, and adorned with hymns and paraphrases to match. He wrote several hymns for young people, many on prayer, and a series on the Beatitudes; he was one of the first to print them on separate pew-sheets rather than ‘lining out’ for a congregation to follow. A favourite device, found in folk-carols but also common at that time, was to use the same (or a similar) last line for each stz as a quasi-refrain, as in 2 of his 3 hymns in Praise!; this however needs a particular writing skill, and risks the thought being dominated by the need to repeat the rhyme each time (see 281). Many hymns anticipate, though with a meatier content, a 20th-c trend to single word repetition in songs; ‘precious’ coming in 13 of 24 lines, or ‘needful’ in 14 of 24 and as the first word in 13 of them. Perhaps by their very inevitability (and both these are Scripture-based) these ‘repeats’ were effective aids to teaching and memory? Sometimes, however, they lead to unfortunate anticlimaxes: ‘And there, in songs for evermore,/ exult in God, and bless this Door’! His letters, too, were often in verse. While in London in 1798 he became ill, though he could still preach back at home. But within a year he was a dying man; his last words were reported as ‘Glory, glory! Home, home!’ He was called ‘a great preacher and small poet’, but like J Hart (qv) he is well represented in Strict Baptist collections such as Denham’s (with 48 texts) and Stevens’s (with at least 32); see the notes to B Beddome. The latter’s edited version of SM’s Wrapped in the silence of the night makes a fine text on ‘the Nativity of Christ’; so does Mortals, awake, with angels join from Gray’s Hymnal of 1895. GH has 9 of his hymns; CH (both edns) has 2. Two rival and somewhat contradictory memoirs were published, by Medley’s son (in 1800) and his daughter Sarah (in 1833). In 1978 the Strict Baptist Historical Society published B A Ramsbottom’s Samuel Medley: Preacher, Pastor, Poet. One notable letter to John Fawcett (qv) has been preserved and reprinted. Nos.259, 462, 687.