Jerusalem the golden

- Genesis 2:9-10

- Genesis 3:22-24

- Exodus 13:5

- Exodus 38

- Leviticus 20:24

- Numbers 13:27

- Deuteronomy 6:3

- Joshua 5:6

- Psalms 122:2-3

- Psalms 122:5

- Psalms 27:4

- Psalms 48:1-2

- Isaiah 33:20

- Isaiah 52:1-2

- Isaiah 60:19-20

- Isaiah 65:18-19

- Isaiah 65:9

- Jeremiah 11:5

- Ezekiel 12:10

- Ezekiel 20:6

- Ezekiel 34:24

- Ezekiel 37:25

- Ezekiel 44:3

- Ezekiel 46:2-4

- Ezekiel 47:12

- Ezekiel 48:30-35

- Joel 3:17

- Zechariah 1:17

- Matthew 24:22-24

- Matthew 24:31

- Mark 13:20

- Mark 13:27

- Luke 18:7

- Acts 3:15

- Acts 5:31

- Acts 7:55-56

- Romans 8:33

- Titus 1:1

- Hebrews 11:16

- Hebrews 12:22-23

- Hebrews 4:9

- 1 Peter 1:2-4

- Revelation 14:1

- Revelation 14:13

- Revelation 2:10

- Revelation 2:7

- Revelation 21:10-11

- Revelation 21:18-25

- Revelation 21:2-4

- Revelation 22:14

- Revelation 22:2

- Revelation 3:4-5

- Revelation 6:11

- Revelation 6:9

- Revelation 7:9-15

- 971

Jerusalem the golden

with milk and honey blessed,

O city of God’s presence,

his people’s promised rest!

I know not, O I know not,

what joys await us there,

what radiancy of glory,

what peace beyond compare!

2. They stand, those halls of Zion,

all jubilant with song;

and bright with many an angel,

and all the martyr throng:

the Prince is ever in them,

the daylight is serene;

the tree of life and healing

has leaves of richest green.

3. There is the throne of David;

and there from pain released,

the shout of those who triumph,

the song of those who feast:

and all who with their leader

have conquered in the fight,

are garlanded with glory

and robed in purest white.

4. How lovely is that city!

the home of God’s elect;

how beautiful the country

that eager hearts expect!

Jesus, in mercy bring us

to that eternal shore

where Father, Son and Spirit

are worshipped evermore.

© In this version Jubilate Hymns

This text has been altered by Praise!

An unaltered JUBILATE text can be found at www.jubilate.co.uk

Bernard of Cluny c.1140

Trans. John Mason Neale 1818-66

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

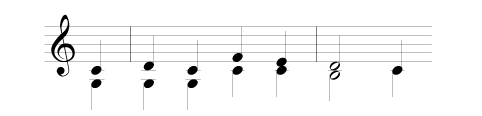

Tune

-

Ewing

Metre: - 76 76 D

Composer: - Ewing, Alexander

The story behind the hymn

At first sight or from an 1849 perspective, John Mason Neale’s work of rediscovery and paraphrase on a vast 12th-c Lat poem on the contempt of the world (De contemptu mundi, itself a ‘miracle of verse’—Dearmer) could seem like a rescue operation, or at best a worthy academic exercise. A glance at 3 of the hymns exhumed and resuscitated for A&M may even confirm that suspicion, though Brief life is here our portion, For thee, O dear, dear country and even The world is very evil all have their supporters, tunes, and other books to confirm their use until recently. With the 4th extract, however, we move (almost literally, certainly spiritually) into a different world, and in the present text we find a truly golden text worthy of the Urbs [urbis] Sion aurea on which it is based, and reflecting something of the ‘golden city of Zion’ which it attempts to portray. The Victorian translator regarded it as the loveliest of medieval Lat poems. The original 2,966 dactylic hexameter lines, dated c1145, carry through a complex rhythm impossible to convey fully in other languages, though Samuel Duffield (son of George who wrote 890) tried in 1867 with These are the latter times, these are not better times: let us stand waiting. They are reliably attributed to Bernard of Cluny, the monastic house near Mâcon, N of Lyon in France. (He has other titles, but is different from his older contemporary and namesake of Clairvaux, 439.) The philologist and later archbishop Richard Chevenix Trench published 96 of Bernard’s lines in his Sacred Latin Poetry in 1849; Neale first paraphrased these, and in 1858 produced a further English version using more of the original in The Rhythm of Bernard de Morlaix, Monk of Cluny, on the Celestial Country. The 4 hymns emerging from that featured as congregational items first in the original A&M, and with this one, most other major books have followed suit. Stz 4, however, is the work of the A&M compilers and has no equivalent in Neale or Bernard.

HTC in 1982 produced a revision which was described as more wooden than golden (or ‘Jerusalem the concrete …’); Praise! and indeed now Jubilate has drawn back from some of its modernised lines; but unavoidable changes from Neale come at 1.3–4 (from ‘beneath thy contemplation/ sink heart and voice opprest’), 1.6 (‘what social joys are …’) and 1.8 (‘peace’ for ‘bliss’); 2.2 (from ‘conjubilant’, direct from the Lat, surviving in EH and its 1986 successor but adjusted by most books as here) and 2.7–8 (‘the pastures of the blessèd/ are decked in glorious sheen’); 3.2 (‘pain’ for ‘care’, the meaning of which has shifted) and 3.7–8 (from ‘for ever and for ever/ are clad in robes of white’—a clear improvement?). The final (A&M) stanza had ‘O sweet and blessèd country’ at lines 1 and 3, and ended, ‘… dear land of rest;/ who art, with God the Father/ and Spirit, ever blest.’ EH, while using 4.1 & 3, ends quite differently, and other variations inevitably appear elsewhere; PHRW, traditional for 3 stzs, has a new ‘evangelical’ final one, ‘The cross is all their splendour,/ the Saviour is their praise,/ his love and his atonement/ the ransomed people raise …’ Scriptures used include the prophecies of ‘the Prince’ in the later part of Ezekiel as well as the familiar imagery of Revelation. It is worth remembering that in the original poem the joys of heaven were set forth in stark contrast to the corruption of the world as perceived some 9 c’s ago: his work began Hora novissima, tempora pessima … As ever, J R Watson has some valuable comments in An Annotated Anthology of Hymns, pp47–49.

It is hard to read the words of this hymn without also ‘hearing’ the tune EWING, and most who love it would never want to separate the text from its ‘proper’ music. It is illuminating therefore to find the A&M Historical Companion listing 4 other tunes, (a-d) before coming to this one at (e); and that the composer Alexander Ewing composed it for Brief life is here our portion or For thee, O dear, dear country. It appeared (in 3/4 time!) on a leaflet in 1853, then in 1857 (named ST BEDE’S) in J Grey’s A Manual of Psalm and Hymn Tunes. Against the preference of its composer, A&M changed the rhythm to 4/4 or Common Time, and established its now almost universal use with these words. Neale (and the children whom he taught) loved it; Archibald Jacob found in it ‘a kind of struggling ecstasy’; Routley called it ‘irreplaceable’ while being ‘not above criticism’ (an echo of Jacob); and commented on the quantity of low-pitched melody and ‘the dramatic ascent to its climax in lines 5–6’. Although the tune has sometimes been set to other words, there is much to be said for some editorial self-control here.

A look at the authors

Bernard of Cluny

(aka B of Morlaix, Morlass, Morval or Murles), b Morlaix, Brittany, France, early 12th c (c1140), d Cluny, Burgundy, France. Born probably of English parents, he became a monk in the community of Cluny, then led by its reforming 8th Abbot, Peter ‘the Venerable’ (c1092–1156), who translated the Koran into Lat, where Bernard seems to have spent the rest of his life. He was renowned in his day as a preacher and author but is now remembered for his 3000-line poem De Contemptu Mundi (‘On Contempt of the World’), on which more than one hymn has been extracted in translation. It attacked not only the world but the worldliness of the church, and was an extended reminder of the transitory nature of all earthly life. (G Currie Martin, first secretary of the Hymn Society, died at Morlaix in its first year, 1937.) See the notes to no.971.

Neale, John Mason

b at Lamb’s Conduit St, Bloomsbury, Middx (C London) 1818, d East Grinstead, Sussex 1866. He was taught privately and at Sherborne Sch; Trinity Coll Cambridge (BA 1840), then Fellow and Tutor at Downing Coll. On 11 occasions he won the annual Seatonian Prize for a sacred poem. Ordained in 1841, he was unable to serve as incumbent of Crawley, Sussex, through ill health, and spent 3 winters in Madeira. He became Warden of Sackville Coll, E Grinstead, W Sussex, from 1846 until his death 20 years later. This was a set of private almshouses; in spite of a stormy relationship with his bishop and others over ‘high’ ritualistic practices, he developed an original and organised system of poor relief both locally and in London, through the sisterhood communities he founded.

With Thos Helmore, Neale compiled the Hymnal Noted in 1852, which did much to remove the tractarian (‘high church’) suspicion of hymns as essentially ‘nonconformist’. Among his many other writings, arising from a vast capacity for reading, was the ground-breaking History of the Eastern Church and the rediscovery and rejuvenating of old carols (collections for Christmas in 1853 and Easter the year following). His untypical, eccentric but popular item Good King Wenceslas was a target for the barbs of P Dearmer, qv, who (like others since) voiced the hope in 1928 that it ‘might be gradually dropped’.

Neale and his immediate circle had a pervasive effect on many things Anglican, including architecture, furnishing and liturgy, which has lasted until our own day. He founded and led the Camden Society and edited the journal The Ecclesiologist in order to give practical local expression to the doctrines of the Tractarians. But his greatest literary work lay in his translation of classic Gk and Lat hymns. In this he pioneered the rediscovery of some of the church’s medieval and earlier treasures, and his academic scholarship blended with his considerable and disciplined poetic gifts which showed greater fluency with the passing years. Like Chas Wesley he was an extraordinarily fast worker, given the high quality of so much of his verse. His translations from Lat, mainly 1852–65, kept the rhythm of the sources; among his original hymns (1842–66) he was critical of his own early attempts to write for children. But he considered that a text in draft should be given plenty of time to mature or be improved; he voluntarily submitted many texts to an editorial committee. Even so, some were attacked by RCs because in translation he had removed some offensive Roman doctrines; others, because they leant too far in a popish direction. His own position was made clear by such gems as, ‘We need not defend ourselves against any charge of sympathising with vulgarity in composition or Calvinism in doctrine’.

Of his final Original Sequences and Hymns (1866), many were written ‘before my illness’, some over 20 years earlier, and ‘the rest are the work of a sick bed’—JMN, writing a few days before his death. His daughter Mary assisted in collecting his work, and many of his sermons were published. He was familiar with some 20 languages, and had a notable ministry among children, writing several children’s books. He had strong views on music, and was a keen admirer of the poetry of John Keble, qv. 72 items (most of them paraphrases) are credited to him in EH, and he has always been wellrepresented in A&M, featuring 30 times in the current (2000) edn, Common Praise. Julian gives him extended treatment and notes ‘the enormous influence Dr Neale has exercised over modern hymnody’. In A G Lough’s significantly titled The Influence of John Mason Neale (1962) and Michael Chandler’s 1995 biography, while the main interest of the writers lies elsewhere, there are interesting chapters respectively on his ‘Hymns, Ballads and Carols’ and his ‘Hymns and Psalms’. What Charles Wesley was with original texts, so was Neale with translations, not least in the sense that, as a contemporary put it, ‘he was always writing’. Nos.225, 297*, 338, 346, 371*, 407, 442, 472, 567, 881, 971.