Jesus, your blood and righteousness

- Job 10:9

- Job 29:14

- Ecclesiastes 3:20

- Isaiah 52:1

- Isaiah 54:5

- Isaiah 61:10

- Daniel 12:2-3

- Zechariah 3:3-5

- Matthew 12:28-29

- Mark 3:27

- Luke 11:20-22

- Luke 15:24

- Luke 15:32

- Luke 21:28

- Luke 4:22

- John 11:43-44

- John 14:2-3

- John 3:16

- John 5:25

- Acts 19:20

- Acts 20:32

- Acts 4:29

- Romans 1:16

- Romans 10:3

- Romans 11:32

- Romans 8:33-34

- 2 Corinthians 13:11

- 2 Corinthians 5:21

- Ephesians 5:14

- 2 Peter 3:10

- 2 Peter 3:7

- 1 John 4:17

- 1 John 5:11

- 778

Jesus, your blood and righteousness

my beauty are, my glorious dress;

mid burning worlds, in these arrayed,

with joy I shall lift up my head.

2. Bold shall I stand on your great day

and none condemn me, try who may;

fully absolved by you I am

from sin and fear, from guilt and shame.

3. When from the dust of death I rise

to claim my home beyond the skies,

then this shall be my only plea:

Jesus has lived, has died for me.

4. O give to all your servants, Lord,

to speak with power your gracious word,

that all who now believe it true

may find eternal life in you.

5. O God of power, O God of love,

let the whole world your mercy prove;

now let your word in all prevail;

Lord, take the spoils of death and hell!

6. O let the dead now hear your voice;

let those once lost in sin rejoice!

Their beauty this, their glorious dress,

Jesus, your blood and righteousness.

© In this version Praise Trust

Nicolaus L Von Zinzendorf 1700-60

Trans. John Wesley 1703-91

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

Tunes

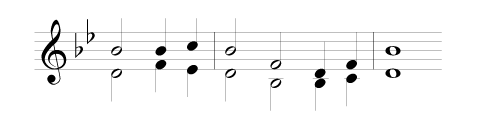

-

Lledrod

Metre: - LM (Long Metre: 88 88)

Composer: - Caniadau Y Cyssegr (1839)

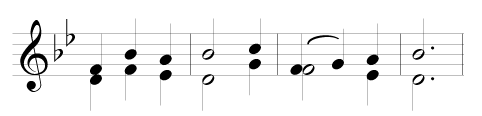

-

Fulda=Walton

Metre: - LM (Long Metre: 88 88)

Composer: - Sacred Melodies

The story behind the hymn

This and the following hymn announce their subject as the ‘blood and righteousness’ of Jesus Christ; from the 18th c, John Wesley’s translation uses the (favourite) image of rescue from fire, whereas for the 19th-c Edward Mote (779) the deliverance is from flood. Other comparisons and contrasts are also suggestive. But the starting-point of this text is the Moravian Count Zinzendorf, whose hymn Christi Blut und Gerechtigkeit was a product of his visit to the Caribbean. He wrote it in 1739 on the tiny Dutch island of St Eustatius near St Kitts, and published in that year in one of the Appendixes to his Herrnhut song-books. Wesley translated 24 of the 33 German stzs, from which varied selections have been made since his 1740 Hymns and Sacred Poems where its title was ‘The Believer’s Triumph.’ The words ‘blood and righteousness’ do not occur together in Scripture, but a blend of Isaiah 61:10 and 2 Corinthians 5:21 has created the familiar phrase, of great power to believers in Christ’s atoning death and imputed goodness. Some editors, including Methodist ones, have emended this line in one direction or another. The main changes made here are in 1.3 (from ‘flaming worlds’) 2.2–3 (‘for who aught to my charge shall lay?/ Fully absolved through these …’); 3.2 (‘my mansion in …’); 4 (‘Ah, give to all, almighty Lord,/ with power to speak … ;/ that all who to thy wounds will flee/ may find eternal life in thee’); and 6.2 (‘Now bid thy banished ones …’). But every edited selection loses some fine lines from Wesley’s original.

Alternative tunes found in other books and listed here are FULDA and WINCHESTER NEW (95 and 348). The Welsh LLEDROD (=LLANGOLLEN), used in CH for this and 503, appeared in Caniadau y Cyssegr (Songs of the Sanctuary), a collection compiled by John Roberts in 1739 exactly 100 years after the words were written. This is described by Cliff Knight as ‘the finest collection for the use of Welsh congregations.’ Alan Luff calls the music ‘tightly constructed … with a strong sense of growth and an exuberance that is especially marked in the third line.’ As he says, it ‘ranges widely up and down the major triad.’ Its name is that of the village SE of Aberystwyth, near the birthplace of Roberts (‘Ieuan Gwyllt’) who was probably at least partly its composer. GH opts for John Eagleton’s stirring tune JUSTIFICATION. John Wesley’s choice for ‘the Foundery’ in 1742 was a variant of TALLIS’ CANON (223).

A look at the authors

Wesley, John

b Epworth, Lincs 1703, d City Rd, Old St, Middx (C London) 1791. As a boy he was dramatically rescued from a fire at his father’s rectory at Epworth; after study at Charterhouse Sch, Surrey, and Christ Church Oxford, he was ordained and elected a Fellow of Lincoln Coll. He became the leader of Oxford’s ‘Holy Club’ which his younger brother Charles (qv) had quite informally begun and which first attracted the nickname ‘Methodist’, in which he later gloried. Its members were active in disciplined religious observances and unusual social commitments such as prison visiting. In 1735 he sailed with Charles and others to Georgia, technically as a missionary, in effect a chaplain, but in either role a self-confessed failure. After some naïve actions complicated by a near-disastrous romantic entanglement, he left in embarrassed humiliation, not before courting a rather different trouble by unauthorised tampering with the texts of familiar hymns. Back in London he built on the Moravian contacts he had made on the outward voyage, notably in friendship with Peter Böhler. After intense struggles to find a personal faith, the decisive moment of conversion came at a meeting in Aldersgate St in May 1738— recorded in detail in his published Journal, now commemorated by Methodists worldwide but strangely seldom mentioned in his later writings. ‘Conversion’ or not, the event had ‘pivotal significance’ (A Skevington Wood) for Wesley and Methodism.

It marked, however, a turning point in his life which from then on became an extraordinary career of sustained energy as a travelling evangelist (usually on horseback), church planter, teacher, author, controversialist, and in effect the founder of a denomination. Technically he remained an Anglican, but he put in place all the structures which led to the inevitable split soon after his death. He followed George Whitefield and brother Charles in ‘field-preaching’, which then became his normal method; they and their colleagues suffered cruel and sometimes near-fatal attacks. While at first keen not to duplicate or rival services provided by each local parish church (from which he was increasingly barred for his evangelical preaching), he established meeting-places, schools, teams of lay preachers, class-meetings, medical clinics, and in 1784 an annual Conference which remains the decision-making centre of Methodism. Not the least cause of division in that year was his ‘ordination’, bishop-style, of Thomas Coke and others to serve in N America, at first under his authority. Sadder, perhaps, were divisions within evangelical ranks; Wesley opposed Whitefield’s preaching of the Reformed ‘doctrines of grace’, upheld free-will and taught the possibility of ‘perfect love’ which he was constantly driven to explain or qualify. Some colleagues became disillusioned with his autocratic style; after Charles intervened to prevent an impending marriage, John married suddenly, unwisely and unhappily. While his relations with women were often problematic, he also attracted deep loyalty from followers of either sex, notably that of the remarkable Elizabeth Ritchie who attended his death-bed. In old age, continuing to travel and preach so long as it was physically possible, he mellowed so far as to become almost an establishment figure, respected by Blake, Johnson and others including royalty. But in social attitudes he remained radical, a fierce opponent of slavery who wrote his Thoughts Upon Slavery in 1774 (long before abolition), a critic of many but not all wars, with a simple lifestyle and a fascinated horror of wealth, grand houses and nobility. He never quite overcame his need to control those around him or take the credit for joint enterprises. Unlike virtually all his contemporary preachers he did not wear a wig. He compiled a popular dictionary, a practical medical handbook, and much more. His work as a hymnwriter, translator, abridger and editor has largely been overshadowed by his other achievements, but in hymnody alone his place in history is assured. Many collections of work by one or both of the brothers named them pointedly as ‘Presbyters of the Church of England’. The authorship of some texts is still disputed, as between John and Charles; Erik Routley is among those who believe that all the original texts are Charles’s, John providing only translations. A great compiler of lists and maker of rules, he naturally provided his Methodists (in 1761) with some pointed ‘Directions for Singing’, which are still commonly and deservedly quoted.

As well as Charles, John’s father and elder brother (both Samuel), his mother Susanna and sister Hetty all had outstanding gifts. There are memorials to him at City Rd, London (his house, chapel and tomb) and in Bristol’s historic ‘New Room’. Among recent biographies, those by S Ayling, R Hattersley and (notably) H Rack are all valuable. JW’s own fascinating Journals, abridged or in full, are indispensable but (like his definitive published sermons) need to be read with discernment; in all his writing, as George Lawton kindly put it, he ‘sat lightly to quotation marks’—and sometimes to facts. Biographers of the 18th-c evangelical leaders tend to take sides; Wesley left behind much more accessible printed material, including ammunition, than those who distanced themselves from his claims, policies and ‘free-will’ doctrines. Some Methodists find it especially hard to see him in proportion or take his critics seriously. See also the notes to Cennick, Perronet, Toplady and C Wesley. Nos.240, 778, 781, 844, 878*.

Zinzendorf, Nicolaus Ludwig von

b Dresden, Germany 1700, d Herrnhut, Saxony 1760. The Adelspädagogium (school) at Halle, 1710–16; Univ of Wittenberg (degree in Law) 1716–19. Born into a wealthy branch of the German nobility, trained in Pietist faith by his aunt and grandmother and inheriting the title of ‘Count’ (of Zinzendorf and Pottendorf) after the early death of his father, after graduation he travelled throughout Europe and in 1721 became court poet and then counsellor of state to the Elector of Saxony at Dresden. He then partly fulfilled his boyhood missionary ambition by establishing an extensive Christian settlement (the ‘Herrnhut’ or ‘Lord’s Shelter’) on his own estate at Berthelsdorf; which from 1727 became his full-time commitment. This included a large chapel, an orphanage, workshops and many other related activities; singing had a prominent place in its worship and the Count’s first Gesangbuch was published for Herrnhut in 1735. Moravian missionaries sent from there travelled widely, taking with them their resilient Moravian faith, firm assurance, and Christ-centred hymns, all of which John Wesley (qv) first encountered en route for America. The Count had a licence to preach from the Theological Faculty at Tübingen and the community had a strict constitution which required a close observance of his rules, but became a refuge for Moravian and other Protestant victims of persecution; in 1737 he became an elected bishop in the Moravian church. Although banished from that time for his strange teachings, he returned in 1748 and remained there until his death, reputedly keeping very little money of his own. He wrote some 2000 hymns, the first at the age of 12 and the last in the week of his death; they are generally marked by pietism or deep personal devotion; 3 are included in the Methodist Hymns and Psalms (1983). These, like many others, were translated by Wesley, who was highly impressed on his visit to Herrnhut in 1738 but later became disillusioned by some features of Moravianism and of the Count’s leadership. Julian gives Zinzendorf an extensive account by James Mearns; GH includes 3 translated texts, while CH finds room for 6. 24 of them (and many more from Herrnhut) are retained in the N American Moravian Book of Worship (1995) which opens with a quotation from him: ‘The hymnal is a kind of response to the Bible, an echo and an extension thereof.’ No.778.