Lord, it is not within my care

- Genesis 39:20-23

- Job 26:14

- Psalms 139:10

- Luke 13:24

- John 10:9

- John 16:30

- John 2:24-25

- John 21:15-17

- John 3:5

- John 4:34

- Acts 20:22-24

- Romans 12:11

- Romans 14:8

- 1 Corinthians 13:12

- 2 Corinthians 5:6-9

- Philippians 1:20-21

- 1 Thessalonians 4:17

- 1 Thessalonians 5:23

- 2 Timothy 4:6-8

- Hebrews 2:14

- Hebrews 4:15-16

- 1 Peter 1:8

- 1 John 3:2

- 764

Lord, it is not within my care

whether I die or live;

to love and serve you is my share,

and this your grace must give.

2. If life is long, I shall be glad

that I may long obey;

if short, then why should I be sad

to soar to endless day?

3. Christ leads me through no darker rooms

than he went through before;

whoever to God’s kingdom comes

must enter by this door.

4. Come, Lord, when grace has made me fit

your holy face to see;

for if your work on earth is sweet,

what will your glory be?

5. My knowledge of that life is small,

the eye of faith is dim;

it is enough that Christ knows all

and I shall be with him.

Richard Baxter 1615-91

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

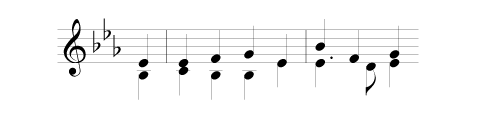

Tune

-

St Hugh

Metre: - CM (Common Metre: 86 86)

Composer: - Hopkins, Edward John

The story behind the hymn

It is not within my power—this is a common thought; Richard Baxter boldly adds that it is not within (or as in his original, does not belong to) his care. Not that he does not care, but that, like the apostle Paul he does not worry; here is another word with a different primary meaning from that of the 17th c. As with other hymns in this section, Philippians 1.20ff is much relied on; as with others by this author, his work is much adapted by hymnal editors. It appeared in Poetical Fragments, Aug 1681, as part of The Concordant Discord of a Broken-healed Heart: London. At the Door of Eternity (see also 590). The first of its eight 8-line stzs began ‘My whole, though broken heart, O Lord …’ His wife had died two months earlier, and in 1689 he called it ‘The Covenant and Confidence of Faith’, adding ‘This covenant my dear wife in her former sickness subscribed with a cheerful will.’ The Companion to Rejoice and Sing says that ‘only the full text of the poem and its context in Baxter’s own experience reveals how much it is a personal statement of faith, rather than an exhortation to others.’ But in the now common selection and arrangement of stzs used here, the 2nd was emended by A&M in 1861, including the added ‘Lord’ at the beginning; there are also changes at 3.3 (from ‘he that into …’) and 4.1–2 (‘… meet/ thy blessèd face …’). One omitted stz is ‘Now I have quit all self-pretence …’; another begins, ‘Then shall I end my sad complaints/ and weary, sinful days …’

Edward J Hopkins’ ST HUGH has proved a serviceable tune for a wide range of hymn texts. They include 444, with which it first appeared in Richard Chope’s The congregational Hymn and Tune Book (2nd edn 1862); it was Arthur Sullivan who set it to Baxter’s words in his 1874 Church Hymns. Of various men dubbed ‘St Hugh’, one was an 11th-c Abbot of Cluny, another the 12th-c Bishop of Lincoln. One of the few tunes composed specifically for these words was Geoffrey Beaumont’s CONTIGO in 1960.

A look at the author

Baxter, Richard

b Rowton, High Ercall, Shrops 1615; d Charterhouse Liberty, Middlesex (London) 1691. Donnington Free Sch, Wroxeter, and private tuition at Ludlow. After a brief time at court he studied theology at home while working on his father’s estate, until becoming master of Dudley Grammar Sch. In 1638 he was ordained, serving first at Bridgnorth (Shrops) and from 1641 at nearby Kidderminster (Worcs). A puritan within the Church of England, he became one of Cromwell’s chaplains but then defended the monarchy against those he saw as usurpers. The Lord Protector, he felt, was too much a Lord, too little a Protector. Later, as chaplain to Chas II, he refused the bishopric of Hereford. In 1662 he left the CofE ministry and was licensed as a Nonconformist minister from 1671. He suffered much harassment, culminating in 18 months’ imprisonment under Judge Jeffreys. But from the Toleration Act of 1689 onwards he was left in peace, and continued preaching and writing for his brief remaining time, earning him the nickname ‘Scribbling Dick’. Baxter also defended church music against some puritan opponents; it is odd to find some 18th-c worthies deriding his friends or successors as ‘Baxterians’ while gladly singing the hymns of Watts and Wesley.

Among some 250 publications were the popular but searching The Saints’ Everlasting Rest, or, a Treatise of the blessed State of the Saints in their Enjoyment of God in Heaven (1649); his ministerial manual The Reformed Pastor (Gildas Salvianus, 1656); and A Call to the Unconverted (1658)—all of which have been frequently reprinted. An ‘abridged and rewritten’ version of the 2nd of these was prepared by Stuart Owen in 1997 with an added 55-page biography, entitled The Ministry We Need. The 3rd was ordered by Samuel Johnson from his bookseller, and when (in 1783) Boswell asked him which of Baxter’s works he should read, the doctor replied, ‘Read any of them; they are all good’. Among others commending Baxter are Doddridge, the Wesleys, Samuel Rutherford, Francis Asbury, Thos Chalmers and Spurgeon; more recently John T Wilkinson has introduced an edited Reformed Pastor (1939) with a 33-page essay; N H Keeble edited Baxter’s autobiography in 1974, and wrote Richard Baxter, Puritan man of Letters, in 1982. His keenest modern admirer James I Packer contributes the feature on him for the 2003 Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals, and several other articles elsewhere; Baxter, says JIP, ‘filled the parish church with over half the population twice a Sunday, saw hundreds of conversions, established family devotions in most homes, nurtured his young people, trained layfolk as witnesses and prayer warriors and, with the help of an assistant, gave every family two separate hours of catechising each year, using the Westminster Shorter Catechism.’ H M Gwatkin said that Baxter and Geo Herbert were ‘the two great model pastors of the 17th century’. Perhaps most remarkably for his time, in confronting the facts of the appalling cruelties of slavery and indeed the institution itself, he enquired in 1673, ‘How cursed a crime it is to equal men to beasts. Is this not your practice? Do you not buy them and use them merely as you do horses to labour for your commodity… Do you not see how you reproach and condemn yourselves while you vilify them as savages?’ It was also Baxter who wrote most quotably (and understandably, given his history) that ‘I preached as never sure to preach again, and as a dying man to dying men.’

But since RB is rarely remembered as a hymnwriter, the treatment of hymns is minimal in or absent from the biographies. His own Saints’ Rest reminds us that ‘Those who have been with us in persecution and prison, shall be with us also in that place of consolation. How oft have our groans made, as it were, one sound; our tears, one stream; and our desires, one prayer! But now all our praises shall make up one melody’. He adds, ‘Be much in the angelical work of praise…The liveliest emblem of heaven that I know upon earth is, when the people of God, in the deep sense of his excellency and bounty, from hearts abounding with love and joy, join together both in heart and voice, in the cheerful and melodious singing of his praises’. Nos.202*, 590, 764.