O sacred head once wounded

- Isaiah 50:6

- Isaiah 52:14

- Isaiah 53:4

- Matthew 26:67-68

- Matthew 27:27-31

- Matthew 27:39-44

- Mark 14:65

- Mark 15:16-20

- Mark 15:29-32

- Mark 15:39-41

- Luke 22:63-65

- Luke 23:11

- Luke 23:35-37

- John 19:2

- John 19:5

- John 20:28

- Acts 4:12

- Romans 3:3

- 2 Corinthians 8:9

- 1 Timothy 1:10

- 1 Timothy 1:15

- 2 Timothy 2:13

- 2 Timothy 4:6-8

- Hebrews 2:14-15

- 1 Peter 2:24

- 439

O sacred head once wounded,

with grief and shame weighed down,

how scornfully surrounded

with thorns, your only crown!

How pale you are with anguish,

with fierce abuse and scorn!

How do those features languish

which once were bright as morn!

2. What bliss was yours in glory,

O Lord of life divine!

I read the amazing story:

I joy to call you mine.

Your grief and your compassion

were all for sinners’ gain;

mine, mine was the transgression,

but yours the deadly pain.

3. What language shall I borrow

to praise you, dearest Friend,

for this your dying sorrow,

your pity without end?

Lord, make me yours for ever!

nor let me faithless prove;

O let me never, never

refuse such dying love!

4. Be near me when I’m dying;

Lord, show your cross to me!

Your death, my hope supplying,

from death shall set me free.

These eyes, new faith receiving,

from Jesus shall not move;

whoever dies believing

dies safely in your love.

© In this version Praise Trust

Paulus Gerhardt 1607-76, From ‘Salve Caput Cruentatum’,

Attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux 1091-1153

Trans. James W Alexander 1804-59

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

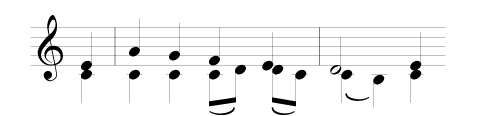

Tune

-

Passion Chorale

Metre: - 76 76 D

Composer: - Hassler, Hans Johann Leo

The story behind the hymn

With this classic hymn we reach a highly composite and truly international text, a tune appropriated from secular use and now virtually inseparable from it, and (continuing with the greatest of all themes) a further personal response to the Saviour’s crucifixion. It has become detached from an original sequence of Lat stzs on parts of the Lord’s body, this one focusing on his ‘sacred head’: Salve caput cruentatum. The attribution to Bernard of Clairvaux in the 12th c rests on its inclusion in his collected works issued in 1609; Paul Gerhardt’s German (O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden) dates from 1656, and James Alexander’s English (or Scots/American) from 1830. Since the 1830 text presents problems for many, others from H W Baker (1861) and Robert Bridges (1899) to Jubilate Hymns (1982) have offered revised versions, and this present one comes from the Praise! editors, gladly acknowledging their debt to earlier writers. The basis, however, is Alexander’s text, 1.1–4 being mainly his (but formerly ‘… now wounded’); the next 12 lines are transposed. 1.5–8 were his 2.5–8, and 2.1–4 his 1.5–8. The second half of stz 2 is from his 3rd; but stzs 3 and 4 are closer to his version. These changes are required by the dropping of 4 lines from his 2nd stz and 4 from his 3rd. The equivalent of 2.1–2 was ‘O sacred head! what glory/ what bliss till now was thine!’, with ‘wondrous’ replaced by ‘amazing’ in the next line.

The tune originated as a love-song (My heart is distracted by a gentle maid) in Hans Hassler’s Lustgarten Neuer Teutscher Gesäng (‘Pleasure-garden of new German songs’) in 1601. But a mere dozen years later it became a hymn tune in the 1613 Harmoniae Sacrae and in 1656 it was set to Gerhardt’s words. In J S Bach’s St Matthew Passion the tune is used 5 times, and thus has been known as PASSION CHORALE, as well as occasionally by its German names. It has also been set to Frances Havergal’s I could not do without you (728). An alternative arrangement is found at 659, but both versions use two of Bach’s harmonisations.

A look at the authors

Bernard of Clairvaux

b ?Les Fontaines, nr Dijon, Burgundy, France 1090, d Clairvaux, France 1153. In 1113 he fulfilled an early ambition when with 30 noblemen, including several of his family, he entered the monastery of Citeaux. Some were husbands leaving behind their wives and children. When after only 2 or 3 years the English abbot Stephen Harding asked him to select a new monastic site, he chose Clairvaux, which soon became a major centre for the Cistercian monks. In 1128 he was secretary to the Synod of Troyes, obtaining official status for the new order of Knights Templar. In 1130 he secured pope Innocent II’s victory against the ‘antipope’ Anacletus, and as a result gained great influence for his order. He practised and preached ascetic self-denial, some claiming that he would have preferred a quiet life of prayer and scholarship, but the following years found him constantly on the move, attacking heresy wherever he saw it, helping to condemn Peter Abelard and Henry of Lausanne, and stirring up what became the second Crusade which began in cruelty and ended in farce. History has given mixed verdicts; to some he was a saintly hero (Thomas Merton’s account is sublimely uncritical) and to others, a dangerous and murderous fanatic. Judged by his writings alone he has left much to move us, including verses not intended to be sung, even when some work previously attributed to him is discounted. Brief selections from his 86 sermons on the Song of Songs begun in 1135, originally running to some 600 pages and reaching a quarter of the way through the book, were re-issued in 1990; this slim volume was based on the 1901 edn, edited by Halcyon Backhouse with a brief biography, for the 900th anniversary of his birth. In the 15th sermon (‘The Name of Jesus’) he says ‘A book or a document has nothing worthwhile in it as far as I am concerned if it does not mention the name of Jesus. I have no interest in conferences where the name of Jesus is not heard. Like honey is to the mouth, melodious music to the ear and a song to the heart, so is the name of Jesus to the soul’. No.439.

Gerhardt, Paulus (Paul)

b Gräfenhainichen, SW of Wittenberg, Germany c1607, d Lübben am Spree, Saxe-Merseburg, 1676. Born to Lutheran parents in an agricultural town, he had many siblings but seems to have been orphaned while quite young. From the age of 15, being proficient in Lat, he attended school at Grimma and from 1628 to c1642 was a student at the Univ of Wittenberg. In 1637 a fire started by Swedish soldiers destroyed his home and all his family records, which has limited our knowledge of his first 30 years, overshadowed as they are with the ‘Thirty Years War’. But for nearly 10 years including some of his happiest, c1643–51, he lived in Berlin where he wrote Gelegenheitsgedichte, 18 items of which his friend J Crüger (qv) included in the Praxis pietatis melica. In 1651, aged 45, he was ordained as provost/pastor at Mittenwalde; he married in 1655 and 2 years later began his pastorate at St Nicholas’ Ch, Berlin. Here the divisions between his own Lutheran faith and the Reformed version became sharper. But in 1666 he was summoned to a consistory court and threatened with deposition; he resigned rather than sign a document supporting the liberal and syncretistic views of the Elector of Brandenburg. In 1668 he was called to Lübben as pastor and archdeacon, where from 1669 he spent his remaining years. The Paul-Gerhardt-Kirche in Lübben has a portrait and a stained glass window depicting him. While remaining firmly Lutheran, his hymns have a rare and deeply personal devotional sweetness not easy to convey in translation; in spite of all its distresses, home means joy, this earth is sweet, heaven is the natural focus and God is above all a Friend. Erik Routley says that with him ‘the truculent note fades; the personal and hopeful note is heard more strongly’, while Catherine Winkworth compares his ‘purest and sweetest expression’ with that of Geo Herbert in England.

His verses range widely in their themes, and while not among the most prolific German hymnwriters, writing some 132 texts, he ranks with the greatest, perhaps second only to Luther. But he was never truly recognised as such in his own day; he simply sang ‘as the bird that sings in the branches’ (Goethe). He adhered to traditional German metrical forms, and Crüger’s successor Johann Georg Ebeling (1637–76) further promoted Gerhardt’s hymns both by setting them to music and by publishing them. They proved surprisingly acceptable to German RC churches, but in translation they were not well-known in England until the mid-19th c, chiefly through Catherine Winkworth (qv) and the versions published by John Kelly (d1890) in 1867. Like the texts of other Germans, not to mention Britons, some of Gerhardt’s ‘flow on for too long, unto they have outgrown their strength’. But Lutherans have prized such hymns as ‘O Jesus Christ,/ thy manger is/ my paradise at which my soul reclineth…’ (1941 trans). Among studies of his life and work, Theodore B Hewitt’s detailed study Paul Gerhardt as a Hymn Writer and his Influence of English Hymnody (Yale and OUP, 1918) is still useful, and lists 31 translators of his work into English up to that time. 9 of these were women, 6 were Americans, and Jn Kelly (who studied at Glasgow and Edinburgh and Bonn) was the most prolific. 9 translations feature in the 2006 Evangelical Lutheran Worship. Since Gerhardt was probably born just 100 years before C Wesley, 2007 saw the 4th centenary of the former and the 3rd of the latter, which were duly celebrated together. Nos.349, 439, 844, 878*.