Praise, O praise our God and King

- Genesis 1:14-18

- Genesis 2:4-6

- Genesis 8:22

- Leviticus 26:3-4

- Deuteronomy 11:11-15

- Deuteronomy 16:16-17

- 1 Chronicles 16:34

- 2 Chronicles 5:13

- 2 Chronicles 7:3

- Ezra 3:11

- Job 38:26-28

- Psalms 100:5

- Psalms 104:13-14

- Psalms 104:19-21

- Psalms 106:1

- Psalms 107:1

- Psalms 117:2

- Psalms 118:1-4

- Psalms 136

- Psalms 145:15-16

- Psalms 147:7-9

- Psalms 19:4-6

- Psalms 29:9

- Psalms 47:6-7

- Psalms 65:9-13

- Psalms 67:5-7

- Psalms 68:9-10

- Jeremiah 33:11

- Matthew 5:45

- Acts 14:14-17

- 2 Corinthians 9:10

- Hebrews 6:7

- 911

Praise, O praise our God and king;

hymns of adoration sing:

For his mercies still endure

ever faithful, ever sure.

2. Praise him that he made the sun

day by day its course to run:

3. And the silver moon by night

shining with its gentle light:

4. Praise him that he gave the rain

to mature the swelling grain:

5. And commands the fruitful field

all its precious crops to yield:

6. Praise him that from sea and land

food is given by his hand:

7. And for peoples far and near

sharing harvests year by year:

8. Glory to our generous King;

glory let creation sing:

Glory to the Father, Son,

and blessed Spirit, Three-in-One.

© In this version Praise Trust

Based on John Milton 1608-74 and Henry W Baker 1821-77

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

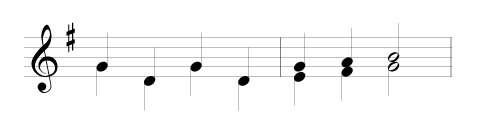

Tune

-

Ephraim

Metre: - 77 77

Composer: - Leslie, Henry Temple

The story behind the hymn

An unknown Hebrew poet, a blind Puritan genius, and an innovative Victorian country vicar combine to launch Praise! into a new section, ‘Christ’s Lordship over all of life’, and its first part: 9a, ‘The earth and harvest’. The roots of this item are in Psalm 136, with its rapid narrative alternating with an insistent refrain, ‘for his mercy [steadfast love] endures for ever’; cf 136 in this book. It is hard to avoid a slight sadness that one of only two hymns attributable to John Milton (and in Praise!, the only one) should be virtually a school exercise, itself needing some marking. He wrote his 24 stzs of Let us with a gladsom mind (golden-tressèd sun, hornèd moon, large-limbed Og and all) when he was rising 16, but has provided the refrain ‘for his mercies ay endure …’, where only one word is changed. His text was written in 1624 (possibly even Dec 1623), published in Poems by Mr John Milton, both English and Latin, Compos’d at several times (1645), but not used in a hymnal before 1855. It was Sir Henry Williams Baker who gave us both a version usable for harvest, at least in 1861 (A&M), and a tune to match. He turned ‘ay’ into ‘still’, and wrote the basis of the text used here, with ‘his’ for the sun and ‘her’ for the moon. Stz 5 was ‘And hath bid … / crops of precious increase yield’; and 8 had ‘bounteous’ (cf 161, stz 2). The 6th and 7th stzs here are new, replacing ‘Praise him for our harvest-store;/ he hath filled the garner floor’; and, ‘And for richer food than this …’ HTC/Jubilate offers virtually a new hymn, still on the Milton/Baker plan. We notice that the Psalm, which this makes no attempt to replace, praises God for both creation and redemption; so do Milton and by implication Baker and Saward (HTC), but only the first is in view here. The Victorian author also provided MONKLAND for his own fresh words and Milton’s revised ones (both printed in A&M), adapted from an early 18th-c German tune and re-named from the Herefordshire parish near Leominster from which he worked to bring hymn-books into a new dimension. The present book, however, chooses the equally vigorous EPHRAIM, composed by Henry T Leslie. It was published in the 1863 Bristol Tune Book (in A major, with no words attached), and in Clifton Conference Hymns (1872) which the composer helped to edit. It has been popular among Methodists (who have preferred Wesley’s words) since 1877, and GH uses it here. In Genesis, Ephraim was a son of Joseph and a half-tribe of Israel.

A look at the authors

Baker, Henry Williams

b Vauxhall, S London, 1821; d Monkland, Herefs 1877. The eldest son of an Admiral and Baronet; Trinity Coll Camb (BA, MA), ordained (CofE) 1844. After a curacy at Great Horkesley nr Colchester, Essex, he became Vicar of the small parish of Monkland (pop c200), a few miles W of Leominster, from 1851 until his death at the age of 56. There being no vicarage, he had one built with space for a private chapel with a small organ; he then established Monkland’s first school. Within his opening few months he had also written his first hymn, published in an 1852 collection made by Francis Murray, Rector of Chislehurst; but greater things were soon afoot. From a crucial meeting at St Barnabas Pimlico, London, in 1858 (see also under Baring-Gould and Woodward) and a formal committee established in the following January, Baker became a founding father of what became Hymns Ancient and Modern. As the project‘s first chairman and its main driving force, he conducted much of the work at and from his vicarage, still in his 30s. After 2 ‘samplers’ in 1859 (the year he inherited his father’s baronetcy) with respectively 50 and 138 hymns, the first official edition including 33 of his own texts and translations appeared in 1861. After an early disappointment Baker never married; but the vicarage, presided over by Henry’s sister Jessy, was a hub of activity often filled with fellow-hymnologists, scholars, editors and workers. They also met regularly at Pimlico, the new railways between London, Leominster, and elsewhere proving a key factor in their work and personal contacts. Baker himself often had to handle tactfully, by post or otherwise, questions of Anglican doctrine, poetic style, copyright terms, payments and fees, textual alterations and (later) how to safeguard its future.

Their book attracted much criticism for editorial changes, but weathered the storm to become the most popular hymn book ever, through main editions of 1868, 1904 (its least successful revision), 1923, 1950, 1983, and 2000. The latest edn, well over a century on, retains 11 of his original texts, versions and translations; 13 are included in the evangelical Anglican Hymn Book of 1965. Among his other writings was Daily Prayers for the Use of those who have to work hard—fittingly from the pen of a man of immense energy and versatility. Julian, who calls his editing labours ‘very arduous’, compares his ‘tender’ and ‘plaintive’ hymnwriting with that of H F Lyte, qv. Among other biographical treatments, he features in Bernard Braley’s Hymnwriters 2 (1989); the 150th anniversary of A&M was celebrated in Monkland and Leominster in 2011. Nos.23C, 371*, 435, 911*, 952*.

Milton, John

b at the Sign of the Spread Eagle in Bread St, Cheapside, London 1608, d St Giles-without-Cripplegate, C London 1674. The son of John senr, a scrivener (secretary/ copyist) and musician, his linguistic and literary gifts blossomed early under his private tutor Thos Young. They then rapidly advanced at St Paul’s Sch, London (where his ‘hymnwriting’ began and virtually ended), and Christ’s Coll Cambridge where he wrote much Latin verse (BA, MA). He wrote his ‘first masterpiece’, the Ode on the Morning of Christ’s Nativity, at the age of 21. From 1632 to 1638 he lived on his father’s estate of Horton, Bucks, where he wrote the constrasting poems L’Allegro and Il Penseroso, the masque Comus and the pastoral and personal elegy Lycidas. Abandoning his plans for Anglican ordination because of what he (and many others) saw as the tyranny of Archbp Laud, he embarked on a dazzling literary, scholarly and political career. After travels in Italy in 1638 he moved to London to teach his widowed sister’s children among others, and in 1641, already a nationally established author, he became a Presbyterian and eventually ‘the fine flower of Puritan humanism’ (Gordon Rupp).

In 1643 he married the teenage royalist Mary Powell, but her early departure, temporary as it proved, influenced his published defence of divorce which in turn led to his split from Presbyterianism. It also provoked Areopagitica (1644), a passionate plea for press freedom and an attack on censorship, because his divorce book was in trouble for its lack of a formal licence. This work of magisterial prose proved highly influential. He now turned to the Independent churches, seeing church divisions as signs of life rather than wounds in the body. In 1645 he and Mary were reconciled; he supported Cromwell’s government from 1649, approved of Charles I’s execution, and accepted a parliamentary position as a ‘Secretary for Foreign Tongues’, drafting Lat letters to foreign governments as well as continuing his literary work, including sonnets in Lat and English. In 1651–52 his advancing blindness became total, and his wife died the following year. Believing that no church should be state-linked or ‘established’, he clashed with Cromwell on that issue and became disillusioned with his leader’s militarism; failing to prevent the return of the monarchy, he was briefly imprisoned at the Restoration.

But from 1658 to 1665 Milton was engaged in writing his 12-book epic Paradise Lost, published in 1667, one of the great poems in (significantly) the English language. Using the classic model established by Homer’s Gk and Virgil’s Lat, and many of their literary devices, he infused the central biblical narrative with his own dramatic and imaginative power, expressed in the sonorous and vividly pictorial language which came to be known as ‘Miltonic’. As with other outstanding Christian authors, notably Jn Bunyan and Wm Cowper (qv), it is necessary to have at least some grasp of and sympathy with the poet’s faith in order to understand his writing. The Christ-centred Paradise Regained and the tragedy Samson Agonistes followed, the latter with poignant reference to the hero’s blindness. His highly individual credal summary appeared posthumously in the less-thanorthodox De Doctrina Christiana. His literary reputation has ebbed and flowed ever since, but he must still be counted one of the finest poets his country has produced; he might have been foreseeing some more recent work in writing that ‘when the vernacular becomes irregular and depraved, there will follow the people’s ruin or their degradation’ (quoted by Charles Cleall, Music and Holiness, 1964). Songs of Praise (1925) used 4 of Milton’s texts as hymns; most hymn-books confine themselves to anything between a half (as here) and two; see notes. His mature poems have the effect of making his ‘hymns’ seem of limited value, but the lyrical quality of even the simpler texts is still apparent. The literature on Milton is appropriately vast; of special interest is C S Lewis’s separately-published Preface to Paradise Lost (1942), not least since ‘given any line in Paradise Lost he could usually continue with the next line’—Derek Brewer. Some of Lewis’s own popular stories for adults and children clearly owe something to Milton. See also the more recent work of Valentine Cunningham and Stanley Fish, among others who have grasped and embraced the ‘Paradise’ plot.

2008 saw many events celebrating the 400th anniversary of the poet’s birth. The Bodleian Library staged an exhibition, ‘Citizen Milton’ and Lance Pierson gave several recitations of ‘Milton in Voice and Verse’. The 16th-cent Grade 1 listed ‘Milton’s Cottage’ in Chalfont St Giles (Bucks) is a permanent memorial housing many treasures. No.911*.