Prayer is the soul's sincere desire

- Nehemiah 1:1-11

- Nehemiah 2:4

- Psalms 119:174

- Psalms 42:1-2

- Psalms 63:1

- Daniel 6:10

- Luke 11:1-4

- Luke 18:13

- Luke 23:42

- John 14:6

- Acts 1:24-25

- Acts 13:1-3

- Acts 14:23

- Acts 16:25

- Acts 7:59-60

- Acts 9:11

- Acts 9:40

- Romans 8:15

- 2 Corinthians 1:11

- Galatians 4:6-7

- Ephesians 6:18

- Hebrews 7:25

- James 5:16-18

- 612

Prayer is the soul’s sincere desire,

expressed in thought or word;

the burning of a hidden fire,

a longing for the Lord.

2. Prayer is the simplest sound we teach

when children learn God’s name;

and yet it is the noblest speech

that human lips can frame.

3. Prayer is the contrite sinner’s voice,

returning from his ways,

while angels in their songs rejoice

and cry, ‘Behold, he prays!’

4. Prayer is the secret battleground

where victories are won;

by prayer the will of God is found

and work for him begun.

5. Prayer is the Christian’s vital breath,

the Christian’s native air,

our watchword at the gates of death;

we enter heaven with prayer.

6. Jesus, by whom we come to God-

the Life, the Truth, the Way-

the humble path of prayer you trod:

Lord, teach us how to pray.

Verses 1-2, 4, 6 © in this version Jubilate Hymns

This text has been altered by Praise!

An unaltered JUBILATE text can be found at www.jubilate.co.uk

James Montgomery 1771-1854

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

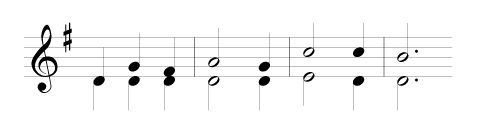

Tune

-

Pastor

Metre: - CM (Common Metre: 86 86)

Composer: - Booth, George

The story behind the hymn

James Montgomery’s second hymn on prayer accompanied the first (610, see note) on his 1818 broadsheet at Sheffield. This one, headed ‘What is Prayer?’, was specifically requested by Edward Bickersteth, who himself made some editorial changes, for his Treatise on Prayer published in 1819. The author said that the hymn was appreciated by his correspondents more than any others he wrote; J R Watson judges it the greatest of all hymns on this subject, ‘wonderfully economical and inclusive’. Those books (including A&M until 2000) which omit it sometimes do so because it is more of a poem than a hymn; the actual prayer comes in the final stz, which the 1951 Congregational Praise (followed by CH) uses also as an opening one, reversing a common device seen (eg) in 387. The original plan is kept here, since other hymns also proceed by statements as well as petitions or praises.

However, changes are made, some following the more radical Jubilate version drafted by Christopher Idle; HTC’s editors would have rejected the hymn unless it could be satisfactorily modified. Montgomery’s 5th word is ‘sincere’ (a significant choice); stz 1 continues, ‘… uttered or unexpressed;/ the motion of a hidden fire/ that trembles in the breast.’ His 2nd, 6th and 7th stzs (‘… the burden of a sigh’, ‘The saints in prayer appear as one’, ‘Nor prayer is made by man alone’) are omitted; his 3rd reads ‘… the simplest form of speech/ that infant lips can try;/ prayer the sublimest strains that reach/ the Majesty on high.’ The original 4th, omitted in HTC, is unchanged here as the 3rd, as is the 5th with the exception of ‘our/we’ for ‘his/he’. (At this point PHRW has ‘seeker’ for ‘Christian’, presumably to reflect Acts 9:10–18, used in stz 3 here, more strictly.) Stz 4 here was written for HTC and included there; the final verse was ‘O thou … the path of prayer thyself hast trod …’ Few books feature all the original 8 stzs. Nearly 50 years before the new stz 4 was drafted, Mildred Cable and Francesca French wrote of ‘those to whom prayer is the battleground where victories are won’ (Ambassadors for Christ, 1935, p42); a phrase CMI was delighted to discover 23 years after his revision. Later still in 2006 he found in Walter Wink’s Engaging the Powers (1992, p297), that prayer ‘may be the interior battlefield where the decisive victory is first won.’

George Booth’s tune PASTOR from 1889 is set in the key of A flat in GH but rarely found elsewhere; nor indeed are any other of his compositions now in evidence in hymn-books. The name has also been given to Geoffrey Beaumont’s 1960 tune for The king of love my shepherd [pastor] is; other music in current use with Montgomery’s words includes BEATITUDO (605) and SONG 67.

A look at the author

Montgomery, James

b Irvine, Ayrshire, Scotland 1771, d Sheffield 1854. His father John was converted through the ministry of John Cennick qv. James, the eldest son, was educated first at the Moravian centre at Fulneck nr Leeds, which expelled him in 1787 for wasting time writing poetry. By this time his parents had left England for mission work in the West Indies. In later life he regularly revisited the school; but having run away from a Mirfield bakery apprenticeship, failed to find a publisher in London, and lost both parents, he served in a chandler’s shop at Doncaster before moving to Sheffield, where from 1792 onwards he worked in journalism. Initially a contributor to the Sheffield Register and clerk to its radical editor, he soon became Asst Editor and (in 1796) Editor, changing its name to the Sheffield Iris. Imprisoned twice in York for his political articles, he was condemned by one jury as ‘a wicked, malicious and seditious person who has attempted to stir up discontent among his Majesty’s subjects’. In his 40s he found a renewed Christian commitment through restored links with the Moravians; championed the Bible Society, Sunday schools, overseas missions, the anti-slavery campaign and help for boy chimney-sweeps, refusing to advertise state lotteries which he called ‘a national nuisance’. He later moved from the Wesleyans to St George’s church and supported Thos Cotterill’s campaign to legalise hymns in the CofE. He wrote some 400, in familiar metres, published in Cotterill’s 1819 Selection and his own Songs of Zion, 1822; Christian Psalmist, or Hymns Selected and Original, in 1825—355 texts plus 5 doxologies, with a seminal ‘Introductory Essay’ on hymnology—and Original Hymns for Public, Private and Social Devotion, 1853. 1833 saw the publication of his Royal Institution lectures on Poetry and General Literature.

In the 1825 Essay he comments on many authors, notably commending ‘the piety of Watts, the ardour of Wesley, and the tenderness of Doddridge’. Like many contemporary editors he was not averse to making textual changes in the hymns of others. He produced several books of verse, from juvenilia (aged 10–13) to Prison Amusements from York and The World before the Flood. Asked which poems would last, he said, ‘None, sir, nothing— except perhaps a few of my hymns’. He wrote that he ‘would rather be the anonymous author of a few hymns, which should thus become an imperishable inheritance to the people of God, than bequeath another epic poem to the world’ on a par with Homer, Virgil or Milton. John Ellerton called him ‘our first hymnologist’; many see him as the 19th century’s finest hymn-writer, while Julian regards his earlier work very highly, the later hymns less so. 20 of his texts including Psalm versions are in the 1916 Congregational Hymnary, and 22 in its 1951 successor Congregational Praise; there are 17 in the 1965 Anglican Hymn Book and 26 in CH. In 2004, Alan Gaunt found 64 of them in current books, and drew attention to one not in use: the vivid account of Christ’s suffering and death in The morning dawns upon the place where Jesus spent the night in prayer. See also Peter Masters in Men of Purpose (1980); Bernard Braley in Hymnwriters 3 (1991) and Alan Gaunt in HSB242 (Jan 2005). Nos.152, 197, 198, 350*, 418, 484, 507, 534, 544, 610, 612, 641, 657*, 897, 959.