Rock of Ages, cleft for me

- Exodus 33:22

- Leviticus 13

- Leviticus 14:13

- Leviticus 16:30

- 2 Samuel 22:3

- Ezra 9:15

- Job 40:4-5

- Psalms 143:9

- Psalms 18:2

- Psalms 27:5

- Psalms 46:1-2

- Psalms 59:16

- Psalms 7:17

- Psalms 94:22

- Isaiah 17:10

- Isaiah 26:4

- Isaiah 49:2

- Isaiah 55:1

- Jeremiah 16:19

- Ezekiel 16:9

- Ezekiel 36:25-27

- Jonah 2:9

- Mark 5:15

- John 13:6-10

- John 19:34-37

- Acts 15:11

- Acts 22:16

- Romans 14:10

- Romans 3:20

- Romans 3:24-25

- Romans 3:27-28

- Romans 5:6-8

- 1 Corinthians 10:4

- 1 Corinthians 6:11

- 2 Corinthians 5:10

- Galatians 2:16

- Ephesians 2:8-9

- 2 Timothy 1:9

- Titus 3:5

- Hebrews 10:23

- Hebrews 11:11

- 1 John 5:6

- Revelation 20:11-13

- Revelation 3:17-18

- Revelation 4:2

- 705

Rock of ages, cleft for me,

hide me now, my refuge be;

let the water and the blood

from your wounded side which flowed,

be for sin the double cure:

cleanse me from its guilt and power.

2. Not the labours of my hands

can fulfil your law’s demands;

could my zeal no respite know,

could my tears for ever flow,

all for sin could not atone:

you must save and you alone.

3. Nothing in my hand I bring,

simply to your cross I cling;

naked, come to you for dress,

helpless, look to you for grace;

stained by sin, to you I cry:

‘Wash me, Saviour, or I die!’

4. While I draw this fleeting breath,

when my eyelids close in death,

when I soar through realms unknown,

bow before your judgement throne:

hide me then, my refuge be,

Rock of ages, cleft for me.

© In this version Jubilate Hymns This is an unaltered JUBILATE text.Other JUBILATE texts can be found at www.jubilate.co.uk

Augustus M Toplady 1740-78

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

Tunes

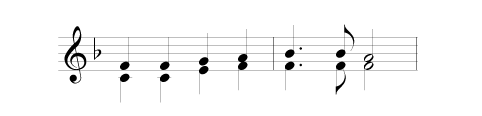

-

Redhead

Metre: - 77 77 77

Composer: - Redhead, Richard

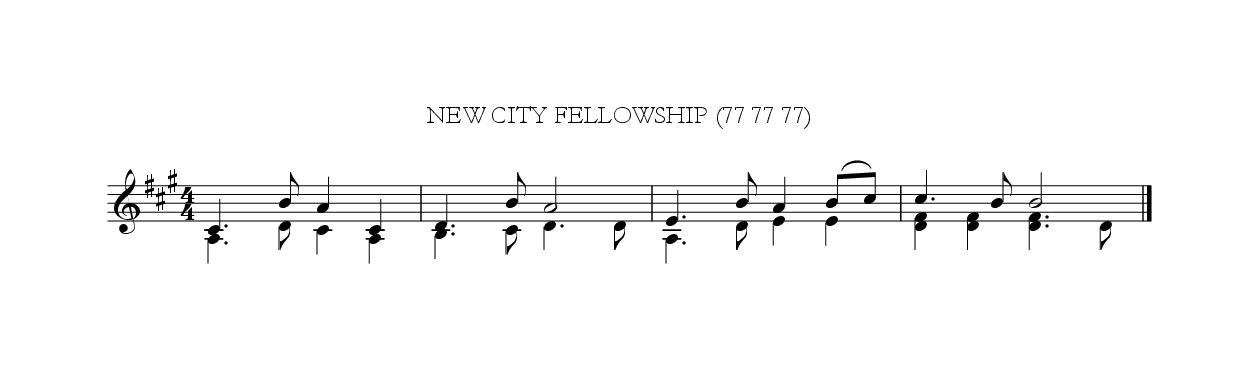

-

New City Fellowship

Metre: - 77 77 77

Composer: - Ward, James C

The story behind the hymn

Few hymns have been praised, blamed or discussed more than this one; by the end of the 19th c, few hymns were more sung, and James King’s 1885 Anglican survey (see below) shows that none was more printed. At about the same time Henry Twells called it ‘the most popular hymn in the English language’. It is acknowledged as the finest from the pen of the prolific, brilliant, and enigmatic Calvinist preacher Augustus Montague Toplady. Although Christ the cleft Rock (1 Corinthians 10:4) and his wounded side (John 19:34–35, 20:20) are the most vivid images presented to us, no text is more fully expounded here than Ephesians 2:8–9. The classic title of the opening 3 words is found in no concordance but its author’s scholarship used the AV Bible’s marginal reading (retained in the RV margin) at Isaiah 26:4—‘for in the LORD JEHOVAH is everlasting strength [RV, ‘an everlasting rock’]; mg, ‘Or a [the] rock of ages’. The title was used in 1740 in Chas Wesley’s Eternal Source of light divine. In the much-debated history of the hymn’s text, we may be certain at least of this: that it began life as a 4-line stz in the Oct 1775 Gospel Magazine, headed ‘Life on a Journey’ and signed ‘Minimus’, that is, its editor Toplady. The first 2 lines have proved crucial and durable; they were incorporated into the 4 stzs appearing in the magazine in the following March; the other 2 lines became 3.5–6. They were headed ‘A Living and Dying Prayer for the Holiest Believer in the World’, and concluded an article by the author (part pulpit illustration, part satire of John Wesley’s Arminian ‘Perfectionism’) entitled ‘A Remarkable Calculation Introduced Here for the Sake of the Spiritual Improvement Subjoined. Questions and Answers, relative to the National Debt.’ The point of these pages was that if the vast ‘National Debt’ was apparently unrepayable, how much less able was any human being to repay the debt to God incurred by a lifetime of our sins, maybe (for those keen on statistics) over 2 1/2 thousand million. In spite of his ongoing debate with Wesley, missed by some over-literal critics of the hymn, it seems likely that Toplady had read an extract from Daniel Brevint, prefaced to Wesley’s Hymns on the Lord’s Supper and determinative for their distinct sacramental theology, which referred to the ‘Rock struck and cleft for me’, ‘Blood and water’, pardon, and holiness. He must also have known Charles’ hymn in that book (omitted from the 1938 reprinted selection), Rock of Israel, cleft for me. By the time of Toplady’s death, to which Wesley responded in a sadly undistinguished way, the hymn was too valuable to omit from Methodist collections, and it reached and sustained enormous popularity in and throughout the 19th c. In his 1885 survey of 52 current hymnals, James King found it in all but one; it thus shared a place in his ‘top 4’ with what here are 223, 359 and 511. Though it has not sustained this position, it still appears in more than 40 current books in Britain alone. The hymn’s many devotees have included hymnwriter James Montgomery, Prince Consort Albert, Prime Minister Gladstone, Professor of English George Saintsbury, author and hymnwriter A C Benson, hymnologist John Julian whose Dictionary gives a very full account, and his recent (2000) biographer George Ella, who regrets that the greatness of Toplady’s verse has eclipsed the merit of his prose works. J R Watson points to the strength of its opening line and closing ‘return’, among other analysis (The English Hymn, 1997, see index). Traditions about a rock at Burrington Combe in Devon where Toplady allegedly sheltered (much earlier than the hymn) have not been traced before c1850 when this was suggested by Dr J Swete, vicar of Blagdon where Toplady was curate 90 years before. See HSB Vol 4 no. 5, Spring 1957. Dearmer concludes that the story was invented ‘perhaps by someone who thought that one little lie would hardly count among a total of 2,552,880,000 sins’. Frank Colquhoun concluded that the secret of the hymn’s popularity lay partly in its ‘vivid and passionate language’ but ultimately in its ‘spiritual qualities and penetrating message’. He quotes H A L Jefferson: ‘The facts of Sin and Grace are not transient modes of theological thought; they are abiding, inescapable verities’ (Hymns that Live, 1980). One change from the original text (4.2, ‘when my eyestrings break in death’) was established as early as 1815; one of the author’s own (4.3, ‘… to worlds unknown’) has proved less popular, though GH and PHRW persevere with it. Even ‘Rock of ages, shelter me…’ knew a brief popularity in some books. The ‘Jubilate’ team, faced with a crucial ‘thee’ in stz 1.2, included it in the handful of hymns in HTC appearing in 2 versions labelled respectively ‘traditional’ and ‘revised’ (eg Praise! 159, 281, 367, 527, 776, 862). It is this revised text which after much discussion is adopted here; main changes come at 1.4 (‘wounded’ for ‘riven’), 3.5 (for ‘foul, I to the fountain fly’) and 4.2–6 (from ‘… tracts/worlds unknown,/ see thee on thy judgement throne—/ Rock of ages, cleft for me,/ let me hide myself in thee.’ (The change at 3.5 is not to deny the foulness but to indicate its source.) Gadsby, who kept ‘eye-strings’ and ‘worlds’ in stz 4, began his version ‘Rock of ages, shelter me’ and also inserted ‘black, I to the fountain fly’. The Brethren Hymns of Light and Love (1900, 1996) has ‘vile’ here, among other alterations. Routley is one of several to note that this text exemplifies the fact that ‘hymnody ignores [usually!] the frontiers set up by religious dispute’; he also says it is the only one of Toplady’s to endure without abridgement— except in some more recent books. The N American Rejoice in the Lord (1985) has 3 altered and rearranged stzs. The words have attracted several tunes, from WELLS (80), Sullivan’s MOUNT ZION, W Rogers’ STRACHAN and Dykes’ TRUST, to James Ward’s American NEW CITY FELLOWSHIP. But two have proved pre-eminent. TOPLADY, in 3/4 time, was named after rather than composed by (as stated in HTC, MP) the author. It is the work of Thomas Hastings, published in 1831 and becoming popular in its native N America as well as in Britain. But the tune by Richard Redhead, published in 1853 in Church Hymn Tunes, Ancient and Modern, for the several seasons of the Christian Year, was also set to this hymn in the first A&M and has weathered musical criticism to retain its popularity ever since. It uses the shape of a Spanish ‘Tantum ergo’, and appears in the keys of D major, E flat or E. The only doubt is in its name, since in various books it appears as REDHEAD (as here), REDHEAD 76 (the number assigned to it in 1853), PETRA (Gk for ‘rock’, named by A&M), AJALON (arbitrary, from Joshua 10:12), GETHSEMANE (from its association with 418), NORWOOD, or HAZEN (unknown). To add confusion, Thos Hastings’ tune was originally known as ROCK OF AGES, was renamed in 1859, and has even been called PETRA as in the Children’s Supplement to the Church Hymnal for the Christian Year.

A look at the author

Toplady, Augustus Montague

b Farnham, Surrey 1740, d Kensington, Middx (W London) 1778. Named after his two godfathers on the insistence of his godmother, he attended Westminster Sch, London (briefly overlapping with the older Wm Cowper) and Trinity Coll Dublin (MA). Like John Wesley whom he later came to oppose, he owed much to his mother, his soldier-father having been killed in a siege before Augustus was born. ‘Mamma’ was also a refuge from an unpleasant aunt, notably during his recurring illnesses. But in 1756, attending a meeting in a barn at the age of 16 in the variously-spelt Cooladine in the parish of Ballynaslaney in the Irish countryside, he was converted through the ministry of James Morris. Morris was a gifted Methodist (later a Baptist) evangelist; a lay preacher but probably not so illiterate as AMT afterwards recalled. The crucial text was Eph 2:13, and his life took a new direction from then onwards. Strengthened in his grasp of Reformed doctrine by feasting on Thos Manton’s printed sermons from John 17 and Geo Whitefield’s preached ones in London, he published a teenage collection of verse in 1759, Poems on Sacred Subjects, with an assured touch but in highly personal ‘I/me’ mode. Without an obvious mentor, a striking opening (‘Chained to the world, to sin tied down’) can descend into absurdity (‘Put on thine helmet, Lord’; ‘O when shall I my God put on?). In 1762 he was ordained in the CofE, but resigned his first parochial charge at Blagdon, Som; he ministered for 16 months at Farleigh Hungerford nr Bradford-on-Avon. A short break was followed by two years in the small and mainly poor villages of Harpford and Venn Ottery, Devon, until he was appointed in 1768, in an exchange of benefices, to Broad Hembury (also spelt as one word), nr Honiton in the same county. Newly recovered from some days of distress and depression (‘the disquietness of my heart’), by now his life was already marked by voracious reading, eloquent preaching, single-minded piety, feverish controversy, occasional hymnwriting, and alarmingly fragile health. His ministry began to achieve remarkable results, but he also fought battles in print with the perfectionism and Arminianism of John and Chas Wesley, writing while standing at his high desk. Where he saw gospel truth at stake, he believed ‘’twere impious to be calm’; 1769 saw the publication of his translation of Jerome Zanchius (1516–90) on predestination, which provoked J Wesley to conspicuous lack of calm in his mocking rejoinder, and so the battle hotted up.

In 1775 Toplady first met Lady Huntingdon and began to preach widely in her chapels, but he was already a sick man. For health reasons he was now able to move from Devon, employing a curate there while he ministered as ‘Lecturer’ at London’s Orange St Chapel in Leicester Fields (between Trafalgar Sq and Leicester Sq) for just over 2 years, the last of his meteoric life as chest pains and other ailments multiplied. This 1693 building was owned and still used by French Reformed Protestants, but licensed for CofE services by the Bp of London, for Toplady’s sake; congregations of both rich and poor overflowed. On 19 April 1778 he could barely croak out his text before withdrawing; it was 2 Pet 1:13–14. But on 14 June, close to death, he spoke with great difficulty, to reaffirm his convictions in the doctrines of grace, which were later printed as a pamphlet. He died two months later at the age of 37, still glorying in Christ but still aiming verbal darts at Wesley, who for his part did nothing to correct the hostile rumours surrounding Toplady’s final hours.

While there were faults and blind spots on both sides, the ‘natural’ friends of Toplady’s doctrinal position now regret that his fiercely-expressed convictions (probably aggravated by illness) provided any justification for John Wesley’s equally aggressive attacks and slanderous accusations. Dr Samuel Johnson remained the friend of both men, and AMT and JW shared an ‘almost uncontrollable passion’ (Lawton) for radically ‘improving’ other people’s hymns—in which they were not alone. Toplady also resembles Chas Wesley in his disciplined rhyming and the occasional indulgence in a rolling Latinism. Occasionally he rises to the heights of Watts; often too a comparable Britishness (identifying the ‘rogue states’ and ‘axis of evil’ of his day) led him into verses rarely sung then, let alone now: ‘Let France and Austria weep in blood;/ just victims of the sword of God’! While maintaining a warm and respectful friendship with Dissenters, notably the Baptist Dr John Gill of Carter Lane, Southwark, Toplady like his other hero Wm Romaine was always fiercely Anglican, appealing often to its Thirty Nine Articles of Religion and other formularies. Part of his own apologia was The Historic Proof of the Doctrinal Calvinism of the Church of England, 700 pages issued in 2 volumes in 1774 to provide theologically heavyweight grounding for the preaching and writing of George Whitefield, who had died in 1770. In 1775 he took over editorship of The Gospel Magazine (‘pompous…pestilential’—J Wesley) for which he wrote, wittily but in the end obsessively, over various initials, until 1777; in 1776 came Psalms and Hymns for Public and Private Worship, which among its 419 items included many vivid Scripture paraphrases (the OT seen through Christian eyes, as in Watts). He lightly revised Cosin’s BCP version of the Veni Creator (see notes on 522) and his ‘Eucharistic’ verses use that adjective in its authentic sense of ‘thanksgiving’ rather than ‘sacramental’.

Reformed hymn-books naturally include more of his hymns than others; Strict Baptists often have a generous share, such as Denham’s 1837 Selection with at least 40 (second only to Newton among CofE contributors). Spurgeon chose 32 of his hymns for Our Own Hymn Book (1866).

But even some who resist his strong doctrines have acknowledged the merit of his writing. Thus while CH has 11 of his hymns and GH 9, Congregational Praise and its successor Rejoice and Sing both find room for 4—three more than A&M, Songs of Praise etc! As in his lifetime, so now, and as with Jn Wesley, it seems hard to arrive at a balanced view of the man and his writing; some hymn-book companions and most Methodist works are hostile, Dr A B Grosart (in Julian) is lukewarm, while other would-be assessors are plainly ignorant. George Ella’s biography (2000) is now essential reading; see also George Lawton, Within the Rock of Ages, 1983, of which Ella is sharply critical. While both are sympathetic, these evangelical biographers have contrasting assessments from AMT’s boyhood onwards. See also Paul E G Cook (the 1978 Evangelical Library Lecture) as well as earlier works. In 1825 Montgomery recognised an ‘ethereal spirit’ in his writing, calling his poetic touch vivid and sparkling; ‘the writer seems absorbed in the full triumph of faith’. One difficulty is that in the 18th and 19th cents, his name became attached to several hymns from other hands; it is among the strangest of some odd omissions from the 2003 Biographical Dictionary of Evangelicals which lists more than 400 others. Nos.705, 711*, 738, 773, 774, 790.