There is a green hill far away

- Hosea 13:4

- Matthew 27:35

- Mark 15:24

- Luke 23:33

- John 13:1

- John 19:18

- Acts 20:28

- 1 Corinthians 15:3-4

- Ephesians 1:7

- Hebrews 13:12

- 1 Peter 2:24

- 1 John 4:19

- Revelation 5:1-5

- 437

There is a green hill far away

outside a city wall,

where our dear Lord was crucified,

who died to save us all.

2. We may not know, we cannot tell

what pains he had to bear,

but we believe it was for us

he hung and suffered there.

3. He died that we might be forgiven,

he died to make us good;

that we might go at last to heaven,

saved by his precious blood.

4. There was no other good enough

to pay the price of sin;

he, only, could unlock the gate

of heaven – and let us in.

5. Lord Jesus, dearly have you loved,

and we must love you too,

and trust in your redeeming blood

and learn to follow you.

Cecil Frances Alexander 1818-95

Downloadable Items

Would you like access to our downloadable resources?

Unlock downloadable content for this hymn by subscribing today. Enjoy exclusive resources and expand your collection with our additional curated materials!

Subscribe nowIf you already have a subscription, log in here to regain access to your items.

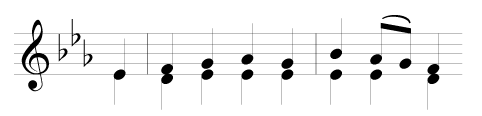

Tune

-

Horsley

Metre: - CM (Common Metre: 86 86)

Composer: - Horsley, William

The story behind the hymn

‘Mrs Alexander is to be spoken of with affection’, wrote Bernard L Manning in 1942, ‘as one of the simplest and purest of writers, but most of all because she wrote There is a green hill and Once in royal David’s city.’ Both were among the 41 Hymns for Little Children published in 1848; this one illustrated the phrase from the Apostles’ Creed, ‘Suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried’, though we may note the absence of any reference to either Pilate or burial, and the inclusion of much more than

credal statement.

In view of the special place the hymn has held as a favourite for over 150 years, it may seem unnecessarily bold or foolish to qualify its commendation. Some, however, have not been slow to highlight the problems this former ‘children’s hymn’ raises; witness the Companions to Songs of Praise and Rejoice and Sing among others. Theologically liberal commentators object most to stz 4; though Erik Routley undertakes a valiant defence of this, and the whole hymn, in Hymns and the Faith (1955; pp119–126). But the first and last lines pose questions too. None of the 4 Gospels mentions a ‘hill’ as the place of crucifixion, let alone its colour, in spite of such poetic licence as is found in 418 (‘mountain’), 424 (‘mount’) and other hymns. Even ‘far away’ (as in the double copying in the lyric of On a hill far away) is now perceived as a relative term only, and was always difficult to sing in Palestine. And how are we to understand the ending, ‘and try his works to do?’ J R Watson, who calls this the author’s ‘greatest hymn’, is well able (like Routley) to defend the text and cope with most of the problems it raises, but even he finds the final line unacceptable: see The English Hymn, 1997, pp434–5.

To change the 1st line would have been fatal, though the 2nd was being altered with the author’s full knowledge (and permission if not agreement) from ‘without a city wall’. 4.3 is partly saved from misunderstanding by the addition of two commas, while the final line is adopted from HTC after various other ways round the difficulty had been tried by the editorial groups of that book and this. As in the Jubilate version, stz 5 is also rendered as a 2nd-person commitment rather than a 3rd-person statement. But the original ‘O dearly, dearly …’ suggests a double meaning, as the love of ‘the/our dear Lord’ (1.3) was both tender and costly. Stz 2 of a traditional ‘May carol’ Awake, awake, good people all, has ‘…for he lovèd us so dear. So dearly, so dearly, has Christ lovèd us, and for our sins was slain…’. American hymnals have not regarded the hymn as indispensable, and a strange and composite irregular paraphrase appeared at Spring Harvest 2006; but Charles Gounod saw it as ‘the most perfect hymn’ in the English language.

This is one of many ‘classics’ where a standard tune has long held a monopoly, but which in the 2nd half of the 20th c have attracted new or different music in order to breathe fresh life into the words, or at least a renewed appreciation of them when sung. But varied tunes have met with uneven acceptance and sometimes proved divisive for the sake of an effect which proves short-lived, so the expected tune is retained here. HORSLEY is named simply after its composer William Horsley; it predates the text, having appeared in 1844 in his Twenty-four Psalm Tunes and Eight Chants. In 1868 it received its name on being included in the Appendix to A&M’s 1st edn, set to the words to which it has been attached ever since.

A look at the author

Alexander, Cecil Frances

b Eccles St, Dublin 1818; d Derry (Londonderry), N Ireland 1895. Born C F Humphreys, given 2 family names (the first given in some reference books as ‘Cecilia’, an understandable error) but always known as Fanny, she showed promise as a writer of verse (stories, amusements, devotions) from her early years. These could be sacred, sentimental, or witty; though never musical, she had a keen sense of sound and rhythm combined with a love of nature and the desire to be a good Anglican. In 1825 the family moved to Redcross, Co Wicklow (the date and place sometimes given for her birth), a ‘lost paradise’ and at that time a private riverside full of wildlife, and in 1833 to the more Protestant neighbourhood of Strabane, in Co Tyrone just south of Londonderry. Deaths in the family, and of 3 teenage sisters who were her friends, left a permanent shadow but also deepened her Christian faith and understanding. Pursuing her studies at home, she developed a good memory and became a fluent French speaker and keen reader. Through the sober godliness of her family and the upper-class company they kept, she ‘cherished into maturity an unshakeable faith in the natural goodness of the nobility’—V Wallace. Yet she also witnessed desperate poverty at first hand, while moving confidently among local and visiting clergy, who took her abilities and conversation seriously and without condescension. She remained most at home with small children and animals, notably dogs; and with her younger sister Anne (Annie) began a lifelong concern for deaf children and those with similar difficulties. Many of her royalties helped to support their care and education. Her frequent travels took her to Scotland and England as well as throughout Ireland.

As for her writing, Verses for Holy Seasons was published in 1846, followed by several other collections including Moral Songs (consciously echoing Watts?) and in 1848 Hymns for Little Children which ran to over 100 editions. By this book she was known; thus Walsham How, listing in a letter of 1869 his fellow guests at the home of the Bp of Oxford, includes ‘the Bishop of Derry with Mrs Alexander (“Hymns for Little Children

204, 372, 437, 842, 857.